In the past month, I’ve spent some time on my album cover classification project. The goal of this project is for me to learn about deep learning by working on an actual problem. This post covers my progress so far, highlighting lessons that would be useful to others who are getting started with deep learning.

Initial steps summary

The following points were discussed in detail in the previous post on this project.

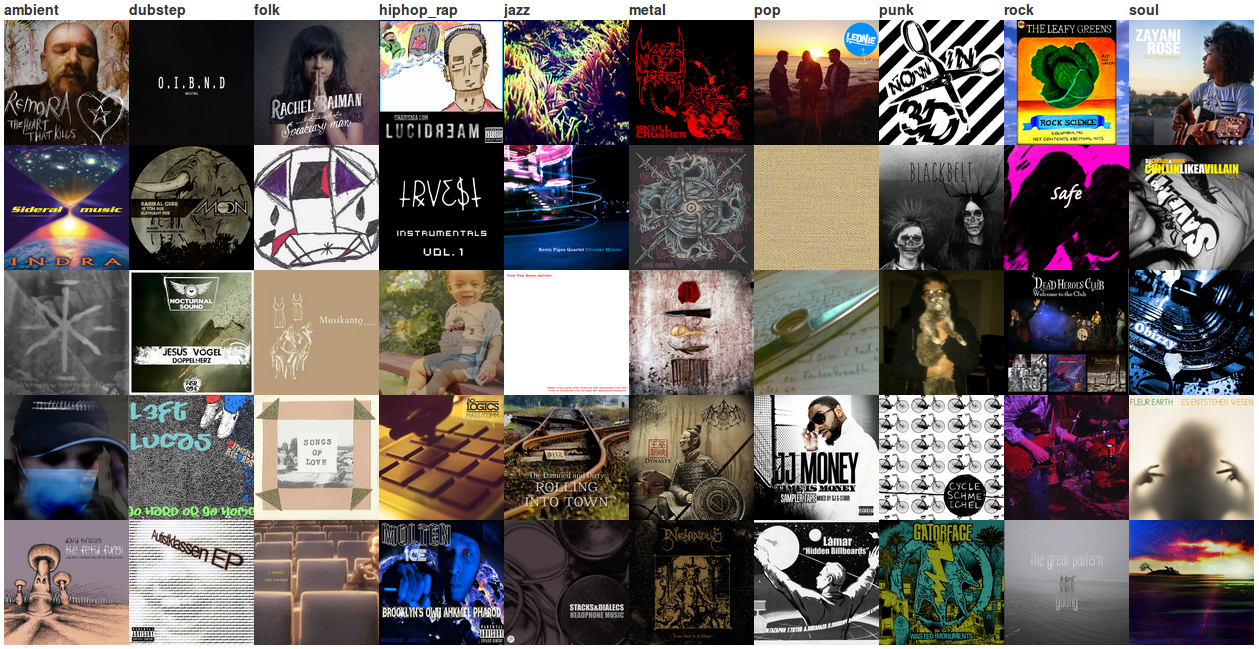

- The problem I chose to work on is classifying Bandcamp album covers by genre, using a balanced dataset of 10,000 images from 10 different genres.

- The experimental code is based on Lasagne, and is available on GitHub.

- Having set up the environment for running experiments on a GPU, the plan was to get Lasagne’s examples working on my dataset, and then iteratively read tutorials/papers/books, implement ideas, play with parameters, and visualise parts of the network until I’m satisfied with the results.

Preliminary experiments and learning resources

I hit several issues when adapting Lasagne’s example code to my dataset. The key issue is that the example code is based on the MNIST digits dataset. That dataset’s images are 28×28 grayscale, and my dataset’s images are 350×350 RGB. This difference led to the training loss quickly diverging when running the example code without any changes. It turns out that simply lowering the learning rate resolves this issue, though the initial results I got were still not much better than random. In general, it appears that everything works on the MNIST digits dataset, so choosing to work on my own dataset made things more challenging (which is a good thing).

The main learning resource I used is the excellent notes for the Stanford course Convolutional Neural Networks for Visual Recognition. The notes are very clear, contain up-to-date information from recent publications, and include many practical tips for successful training of convolutional networks (convnets). In addition, I read some other tutorials and a few papers. These are summarised in a separate page.

The first step after getting the MNIST examples working on my dataset was to extend the code to enable more flexible architectures. My main focus was on vanilla convnets, i.e., networks with several convolutional layers, where each convolutional layer is optionally followed by a max-pooling layer, and the convolutional layers are followed by multiple dense/fully-connected layers and dropout layers. To allow for easy experimentation, the specification of the network can be done from the command line. For example, to train an AlexNet architecture:

$ python manage.py run_experiment \

--dataset-path /path/to/dataset \

--model-architecture ConvNet \

--model-params num_conv_layers=5:num_dense_layers=2:lc0_num_filters=48:lc0_filter_size=11:lc0_stride=4:lc0_mp=True:lm0_pool_size=3:lm0_stride=2:lc1_num_filters=128:lc1_filter_size=5:lc1_mp=True:lm1_pool_size=3:lm1_stride=2:lc2_num_filters=192:lc2_filter_size=3:lc3_num_filters=192:lc3_filter_size=3:lc4_num_filters=128:lc4_filter_size=3:lc4_mp=True:lm4_pool_size=3:lm4_stride=2:ld0_num_units=2048:ld1_num_units=2048

This can obviously be a bit of a mouthful, so common architectures are also defined in the code with parameters that can be overridden. For instance, to train an AlexNet with 64 filters in the first layer instead of 48:

$ python manage.py run_experiment \

--dataset-path /path/to/dataset \

--model-architecture AlexNet \

--model-params lc0_num_filters=64

There are many more command line flags (possibly too many), which make it easy to both tinker with various settings, and also run more rigorous experiments. My initial tinkering with convnets didn’t yield impressive results in terms of predictive accuracy on my dataset. It turned out that this was partly due to the lack of preprocessing – the less exciting but crucial part of any predictive modelling work.

The importance of preprocessing

My initial focus was on getting things to work on the dataset without worrying too much about preprocessing. I haven’t done any image classification work in the past, so I had to learn about the right type of preprocessing to use. I kept it pretty simple and applied the following transformations:

- Downsampling: all images were scaled down to 256×256. I played briefly with other sizes, but decided on this size to make it easy to use models pretrained on ImageNet.

- Cropping & mirroring: during training time, each image was cropped to random 224×224 slices. Deterministic slices were used in test time. In addition, each crop was mirrored horizontally. In most cases I used ten overall crops. Again, these numbers were chosen for comparability with ImageNet-trained models.

- Mean subtraction: the training mean of each pixel was subtracted from each instance.

- Shuffling: probably the most important preprocessing step. Initially I had the instances sorted by their class, as an artifact of the way the dataset was constructed. Due to the relatively small number of instances the network sees in each batch, this meant that in each epoch, the network first fitted on all the instances from class 1, then all the instances from class 2, etc. This led to very poor performance, which was fixed by shuffling the data once at the start of the training procedure (shuffling every epoch could potentially make things even better).

Baselines

After building the experimental environment and a fair bit of tinkering, I decided it was time for some more serious experiments. The results of my initial games were rather disappointing – slightly better than a random baseline, which yields an accuracy score of 10%. Therefore, I ran some baselines to get an idea of what’s possible on this dataset.

The first baseline I tried was a random forest with 1,000 trees, which yielded 15.25% accuracy. This baseline was trained directly on the pixel values without any preprocessing other than downsampling. It’s worth noting that the downsampling size didn’t make much of a difference to this baseline (I tried a few values in the range 50×50-350×350). This baseline was also not particularly sensitive to whether RGB or grayscale values were used to represent the images.

The next experiments were with baselines that utilised pretrained Caffe models. Training a random forest with 1,000 trees on features extracted from the highest fully-connected layer (fc7) in the CaffeNet and VGGNet-19 models yielded accuracies of 16.72% and 16.40% respectively. This was pretty disappointing, as I expected these features to perform much better. The reason may be that album covers are very different from ImageNet images, and the representations in fc7 are too specific to ImageNet. Indeed, when fine-tuning the CaffeNet model (following the procedure outlined here), I got the best accuracy on the dataset: 22.60%. Using Caffe to train the same network from scratch didn’t even get close to this accuracy. However, I didn’t try to tune Caffe’s learning parameters. Instead, I went back to running experiments with my code.

It’s worth noting that the classes identified by the CaffeNet model often have little to do with the actual content of the image. Better baseline results may be obtained by using models that were pretrained on a richer dataset than ImageNet. The following table presents three example covers together with the top-five classes identified by the CaffeNet model for each image. The tags assigned by Clarifai’s API are also presented for comparison. From this example, it looks like Clarifai’s model is more successful at identifying the correct elements than the CaffeNet model, indicating that a baseline that uses the Clarifai tags may yield competitive performance.

| Album | CaffeNet | Clarifai |

|---|---|---|

October by Wille P | digital clock, spotlight, jack-o’-lantern, volcano, traffic light | tree, landscape, sunset, desert, sun, sunrise, nature, evening, sky, travel |

Demo by Blackrat | spider web, barn spider, chain, bubble, fountain | skull, bone, nobody, death, vector, help, horror, medicine, black and white, tattoo |

| dishrag, paper towel, honeycomb, envelope, chain mail | symbol, nobody, sign, illustration, color, flag, text, stripes, business, character |

Training from scratch

My initial experiments were with various convnet architectures, where I manually varied the filter sizes and number of layers to have a reasonable number of parameters and ensure that the model is trainable on a GPU with 4GB of memory. As mentioned, this approach yielded unimpressive results. Following the relative success of the fine-tuned CaffeNet baseline, I decided to run more rigorous experiments on variants of AlexNet (which is very similar to CaffeNet).

Given the large number of hyperparameters that need to be set when training deep convnets, I realised that setting values manually or via grid search is unlikely to yield the best results. To address this, I used hyperopt to search for the best configuration of values. The hyperparameters that were included in the search were the learning method (Nesterov momentum versus Adam with their respective parameters), the learning rate, whether crops are mirrored or not, the number of crops to use (1 or 5), dropout probabilities, the number of hidden units in the fully-connected layers, and the number of filters in each convolutional layer.

Each configuration suggested by hyperopt was trained for 10 epochs, and the promising setups were trained until results stopped improving. The results of the search were rather disappointing, with the best accuracy being 17.19%. However, I learned a lot by finding hyperparameters in this manner – in the past I’ve only used a combination of manual settings with grid search.

There are many possible reasons for why the results are so poor. It could be that there’s just too little data to train a good classifier, which is supported by the inability to beat the fine-tuned results. This is in line with the results obtained by Zeiler and Fergus (2013), who found that convnets pretrained on ImageNet performed much better on the Caltech-101 and Caltech-256 datasets than the same networks trained from scratch. However, it could also be that I just didn’t run enough experiments – I definitely feel like I haven’t explored everything as well as I’d like. In addition, I’m still building my intuition for what works and why. I should work more on visualising the way the network learns to uncover more hidden gotchas in addition to those I’ve already found. Finally, it could be that it’s just too hard to distinguish between covers from the genres I chose for the study.

Ideas for future work

There are many avenues for improving on the work I’ve done so far. The code could definitely be made more robust and better tested, optimised and parallelised. It would be worth investing more in hyperparameter and architecture search, including incorporation of ideas from non-vanilla convnets (e.g., GoogLeNet). This search should be guided by visualisation and a deeper understanding of the trained networks, which may also come from analysing class-level accuracy (certain genres seem to be easier to distinguish than others). In addition, more sophisticated preprocessing may yield improved results.

If the goal were to get the best possible performance on my dataset, I’d invest in establishing the human performance baseline on the dataset by running some tests with Mechanical Turk. My guess is that humans would perform better than the algorithms tested so far due to access to external knowledge. Therefore, incorporating external knowledge in the form of manual features or additional data sources may yield the most substantial performance boosts. For example, text on an album cover may contain important clues about its genre, and models pretrained on style datasets may be more suitable than ImageNet models. In addition, it may be beneficial to use a model to detect multiple elements in images where the universe is not restricted to ImageNet classes. This approach was taken by Alexandre Passant, who used Clarifai’s API to tag and classify doom metal and K-pop album covers. Finally, using several different models in an ensemble is likely to help squeeze a bit more accuracy out of the dataset.

Another direction that may be worth exploring is using image data for recommendation work. The reason I chose to work on this problem was my exposure to album covers through my work on Bandcamp Recommender – a music recommendation system. It is well-known that visual elements influence the way users interact with recommender systems. This is especially true in Bandcamp Recommender’s case, as users see the album covers before they choose to play them. This leads me to conjecture that considering features that describe the album covers when generating recommendations would increase user interaction with the system. However, it’s hard to tell whether it’d increase the overall relevance of the results. You can’t judge an album by its cover. Or can you…?

Conclusion

While I’ve learned a lot from working on this project, there’s still much more to discover. It was especially great to learn some generally-applicable lessons about hyperparameter optimisation and improvements to vanilla gradient descent. Despite the many potential ways of improving performance on my dataset, my next steps in the field would probably include working on problems for which obtaining a good solution is feasible and useful. For example, I have some ideas for applications to marine creature identification.

Feedback and suggestions are always welcome. Please feel free to contact me privately or via the comments section.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Brian Basham and Diogo Moitinho de Almeida for useful tips and discussions.

Public comments are closed, but I love hearing from readers. Feel free to contact me with your thoughts.