A few months ago I participated in the Kaggle Greek Media Monitoring competition. The goal of the competition was doing multilabel classification of texts scanned from Greek print media. Despite not having much time due to travelling and other commitments, I managed to finish 6th (out of 120 teams). This post describes my approach to the problem.

Data & evaluation

The data consists of articles scanned from Greek print media in May-September 2013. Due to copyright issues, the organisers didn’t make the original articles available – competitors only had access to normalised tf-idf representations of the texts. This limited the options for doing feature engineering and made it impossible to consider things like word order, but it made things somewhat simpler as the focus was on modelling due to inability to extract interesting features.

Overall, there are about 65K texts in the training set and 35K in the test set, where the split is based on chronological ordering (i.e., the training articles were published before the test articles). Each article was manually labelled with one or more labels out of a set of 203 labels. For each test article, the goal is to infer its set of labels. Submissions were ranked using the mean F1 score.

Despite being manually annotated, the data isn’t very clean. Issues include identical texts that have different labels, empty articles, and articles with very few words. For example, the training set includes ten “articles” with a single word. Five of these articles have the word 68839, but each of these five was given a different label. Such issues are not unusual in Kaggle competitions or in real life, but they do limit the general usefulness of the results since any model built on this data would fit some noise.

Local validation setup

As mentioned in previous posts (How to (almost) win Kaggle competitions and Kaggle beginner tips) having a solid local validation setup is very important. It ensures you don’t waste time on weak submissions, increases confidence in the models, and avoids leaking information about how well you’re doing.

I used the first 35K training texts for local training and the following 30K texts for validation. While the article publication dates weren’t provided, I hoped that this would mimic the competition setup, where the test dataset consists of articles that were published after the articles in the training dataset. This seemed to work, as my local results were consistent with the leaderboard results. I’m pleased to report that this setup allowed me to have the lowest number of submissions of all the top-10 teams 🙂

Things that worked

I originally wanted to use this competition to play with deep learning through Python packages such as Theano and PyLearn2. However, as this was the first time I worked on a multilabel classification problem, I got sucked into reading a lot of papers on the topic and never got around to doing deep learning. Maybe next time…

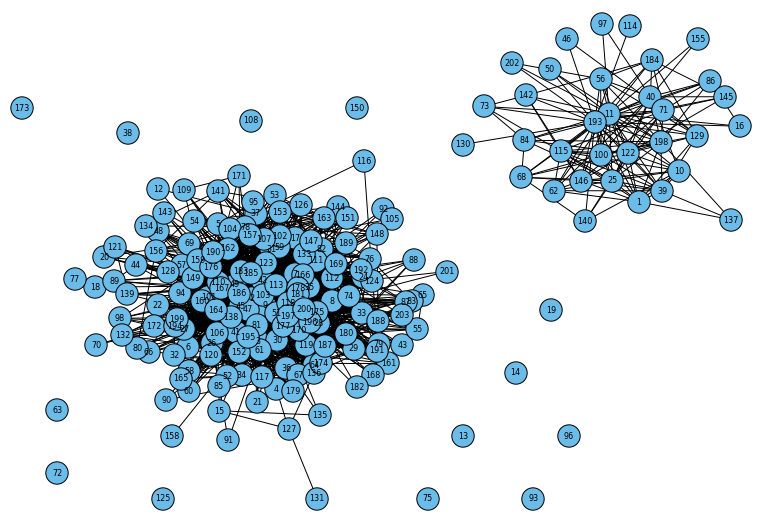

One of my key discoveries was that there if you define a graph where the vertices are labels and there’s an edge between two labels if they appear together in a document’s label set, then there are two main connected components of labels and several small ones with single labels (see figure below). It is possible to train a linear classifier that distinguishes between the components with very high accuracy (over 99%). This allowed me to improve performance by training different classifiers on each connected component.

My best submission ended up being a simple weighted linear combination of three models. All these models are hierarchical ensembles, where a linear classifier distinguishes between connected components, and the base models are trained on texts from a single connected component. These base models are:

- Ensemble of classifier chains (ECC) with linear classifiers (SGDClassifier from scikit-learn) trained for each label, using hinge loss and L1 penalty

- Same as 1, but with modified Huber loss

- A linear classifier with modified Huber loss and L1 penalty that predicts single label probabilities

For each test document, each one of these base models yields a score for each label. These scores are weighted and thresholded to yield the final predictions.

It was interesting to learn that a relatively-simple model like ECC yields competitive results. The basic idea behind ECC is to combine different classifier chains. Each classifier chain is also an ensemble where each base classifier is trained to predict a single label. The input for each classifier in the chain depends on the output of preceding classifiers, so it encodes dependencies between labels. For example, if label 2 always appears with label 1 and the label 1 classifier precedes the label 2 classifier in the chain, the label 2 classifier is able to use this dependency information directly, which should increase its accuracy (though it is affected by misclassifications by the label 1 classifier). See Read et al.’s paper for a more in-depth explanation.

Another notable observation is that L1 penalty worked well, which is not too surprising when considering the fact that the dataset has 300K features and many of them are probably irrelevant to prediction (L1 penalty yields sparse models where many features get zero weight).

Things that didn’t work

As I was travelling, I didn’t have much time to work on this competition over its two final weeks (though this was a good way of passing the time on long flights). One thing that I tried was understanding some of the probabilistic classifier chain (PCC) code out there by porting it to Python, but the results were very disappointing, probably due to bugs in my code. I expected PCC to work well, especially with the extension for optimising the F-measure. Figuring out how to run the Java code would have probably been a better use of my time than porting the code to Python.

I also played with reverse-engineering the features back to counts, but it was problematic since the feature values are normalised. It was disappointing that we weren’t at least given the bag of words representations. I also attempted to reduce the feature representation with latent Dirichlet allocation, but it didn’t perform well – possibly because I couldn’t get the correct word counts.

Conclusion

Overall, this was a fun competition. Despite minor issues with the data and not having enough time to do everything I wanted to do, it was a great learning experience. From reading the summaries by the other teams, it appears that other competitors enjoyed it too. As always, I highly recommend Kaggle competitions to beginners who are trying to learn more about the field of data science and predictive modelling, and to more experienced data scientists who want to improve their skills.

Public comments are closed, but I love hearing from readers. Feel free to contact me with your thoughts.