Messy data, buggy software, but all in all a good learning experience...

Early last year, I had some free time on my hands, so I decided to participate in yet another Kaggle competition. Having never done any price forecasting work before, I thought it would be interesting to work on the Blue Book for Bulldozers competition, where the goal was to predict the sale price of auctioned bulldozers. I’ve done alright, finishing 9th out of 476 teams. And the experience did turn out to be interesting, but not for the reasons I expected.

Data and evaluation

The competition dataset consists of about 425K historical records of bulldozer sales. The training subset consists of sales from the 1990s through to the end of 2011, with the validation and testing periods being January-April 2012 and May-November 2012 respectively. The goal is to predict the sale price of each bulldozer, given the sale date and venue, and the bulldozer’s features (e.g., model ID, mechanical specifications, and machine-specific data such as machine ID and manufacturing year). Submissions were scored using the RMSLE measure.

Early in the competition (before I joined), there were many posts in the forum regarding issues with the data. The organisers responded by posting an appendix to the data, which included the “correct” information. From people’s posts after the competition ended, it seems like using the “correct” data consistently made the results worse. Luckily, I discovered this about a week before the competition ended. Reducing my reliance on the appendix made a huge difference in the performance of my models. This discovery was thanks to a forum post, which illustrates the general point on the importance of monitoring the forum in Kaggle competitions.

My approach: feature engineering, data splitting, and stochastic gradient boosting

Having read the forum discussions on data quality, I assumed that spending time on data cleanup and feature engineering would give me an edge over competitors who focused only on data modelling. It’s well-known that simple models fitted on more/better data tend to yield better results than complex models fitted on less/messy data (aka GIGO – garbage in, garbage out). However, doing data cleaning and feature engineering is less glamorous than building sophisticated models, which is why many people avoid the former.

Sadly, the data was incredibly messy, so most of my cleanup efforts resulted in no improvements. Even intuitive modifications yielded poor results, like transforming each bulldozer’s manufacturing year into its age at the time of sale. Essentially, to do well in this competition, one had to fit the noise rather than remove it. This was rather disappointing, as one of the nice things about Kaggle competitions is being able to work on relatively clean data. Anomalies in data included bulldozers that have been running for hundreds of years and machines that got sold years before they were manufactured (impossible for second-hand bulldozers!). It is obvious that Fast Iron (the company who sponsored the competition) would have obtained more usable models from this competition if they had spent more time cleaning up the data themselves.

Throughout the competition I went through several iterations of modelling and data cleaning. My final submission ended up being a linear combination of four models:

- Gradient boosting machine (GBM) regression on the full dataset

- A linear model on the full dataset

- An ensemble of GBMs, one for each product group (rationale: different product groups represent different bulldozer classes, like track excavators and motor graders, so their prices are not really comparable)

- A similar ensemble, where each product group and sale year has a separate GBM, and earlier years get lower weight than more recent years

I ended up discarding old training data (before 2000) and the machine IDs (another surprise: even though some machines were sold multiple times, this information was useless). For the GBMs, I treated categorical features as ordinal, which sort of makes sense for many of the features (e.g., model series values are ordered). For the linear model, I just coded them as binary indicators.

The most important discovery: stochastic gradient boosting bugs

This was the first time I used gradient boosting. Since I was using so many different models, it was hard to reliably tune the number of trees, so I figured I’d use stochastic gradient boosting and rely on out-of-bag (OOB) samples to set the number of trees. This led to me finding a bug in scikit-learn: the OOB scores were actually calculated on in-bag samples.

I reported the issue to the maintainers of scikit-learn and made an attempt at fixing it by skipping trees to obtain the OOB samples. This yielded better results than the buggy version, and in some cases I replaced a plain GBM with an ensemble of four stochastic GBMs with subsample ratio of 0.5 and a different random seed for each one (averaging their outputs).

This wasn’t enough to convince the maintainers of scikit-learn to accept the pull request with my fix, as they didn’t like my idea of skipping trees. This is for a good reason — obtaining better results on a single dataset should be insufficient to convince anyone. They ended up fixing the issue by copying the implementation from R’s GBM package, which is known to underestimate the number of required trees/boosting iterations (see Section 3.3 in the GBM guide).

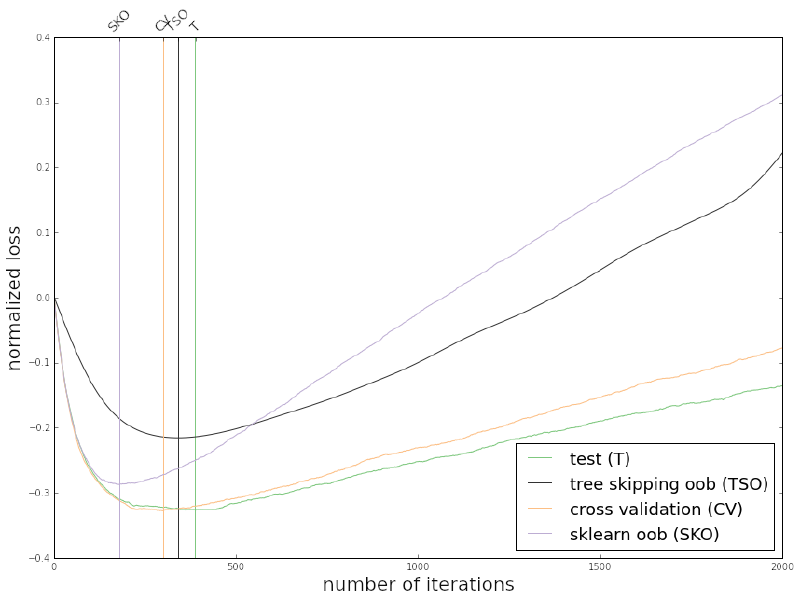

Recently, I had some time to test my tree skipping idea on the toy dataset used in the scikit-learn documentation. As the following figure shows, a smoothed variant of my tree skipping idea (TSO in the figure) yields superior results to the scikit-learn/R approach (SKO in the figure). The actual loss doesn’t matter — what matters is where it’s minimised. In this case TSO obtains the closest approximation of the number of iterations to the value that minimises the test error, which is a promising result.

These results are pretty cool, but this is still just a toy dataset (though repeating the experiment with 100 different random seeds to generate different toy datasets yields similar results). The next steps would be to repeat Ridgeway’s experiments from the GBM guide on multiple datasets to see whether the results generalise well, which will be the topic of a different post. Regardless of the final outcomes, this story illustrates the unexpected paths in which a Kaggle competition can take you. No matter what rank you end up obtaining and regardless of your skill level, there’s always something new to learn.

Update: I ran Ridgway’s experiments. The results are discussed in Stochastic Gradient Boosting: Choosing the Best Number of Iterations.

Public comments are closed, but I love hearing from readers. Feel free to contact me with your thoughts.