You’re a hotshot manager. You love your dashboards and you keep your finger on the beating pulse of the business. You take pride in using data to drive your decisions rather than shooting from the hip like one of those old-school 1950s bosses. This is the 21st century, and data is king. You even hired a sexy statistician or data scientist, though you don’t really understand what they do. Never mind, you can proudly tell all your friends that you are leading a modern data-driven team. Nothing can go wrong, right? Incorrect. If you don’t pay attention, data can drive you off a cliff. This article discusses seven of the ways this can happen. Read on to ensure it doesn’t happen to you.

1. Pretending uncertainty doesn’t exist

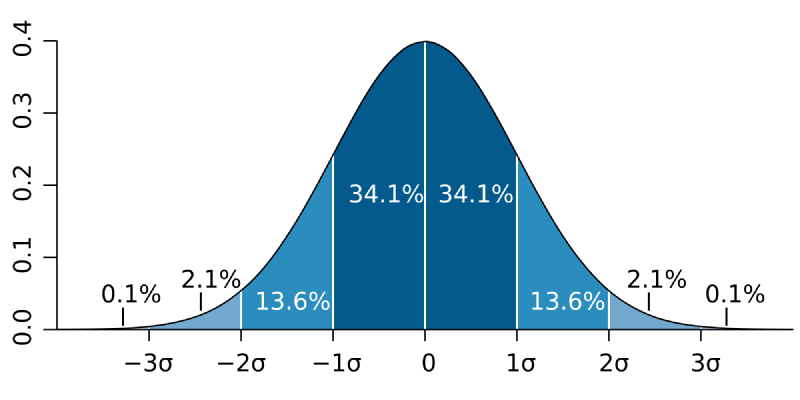

Source: Standard error, Wikipedia

Last month, your favourite metric was 5.2%. This month, it’s 5.5%. Looks like things are getting better – you must be doing something right! But is 5.5% really different from 5.2%? All things being equal, you should expect some variability in most of your metrics. The values you see are drawn from a distribution of possible values, which means you can’t be certain what value you’ll be seeing next. Fortunately, with more data you would be able to quantify this uncertainty and know which values are more likely. Don’t fear or ignore uncertainty. Embrace and study it, and you’ll be on the right track.

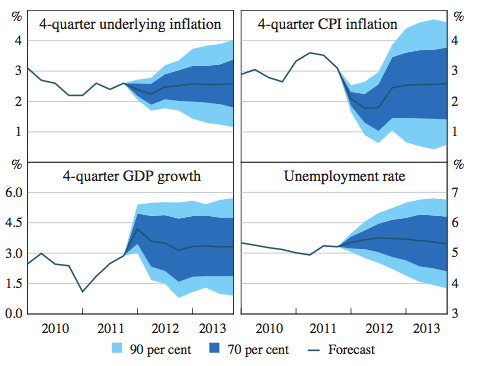

2. Confusing observed and unobserved quantities

Everyone agrees that the future is uncertain. We can generate forecasts with varying degrees of confidence, but we never know for sure what’s going to happen. However, some people tend to ignore uncertainty in forecasts, treating the unobserved future values as comparable to observed present values. For example, marketers often compare customer lifetime value with the cost of acquiring a customer. The problem is that customer lifetime value relies on a prediction of the net profit from a customer (so it’s largely unobserved and uncertain), while the business has much more control and certainty around the cost of acquiring a customer (though it’s not completely known). Treating the two values as if they’re observed and known is risky, as it can lead to major financial losses.

3. Thinking that your data is correct

Ask anyone who works with data, and they’ll tell you that it’s always messy. A well-known saying among data scientists is that 80% of the work is data cleaning and the other 20% is complaining about data cleaning. Hence, it’s likely that at least some of the figures you’re relying on to make decisions are somewhat inaccurate. However, it’s important to remember that this doesn’t make the data completely useless. But if something looks too good to be true, it probably isn’t true. Finally, it’s highly unlikely that the data is always correct when you like the results and always incorrect when the results aren’t favourable, so don’t use the “guy on the internet said our data isn’t 100% correct” excuse to push back on inconvenient truths.

4. Believing that your data is complete

No matter how big you are, your data doesn’t capture everything your customers do. Even Google and the NSA don’t have a full view of what people are up to in the non-digital world, and they can’t completely read our minds (yet). Most businesses have much less data than the big tech companies, and they look a bit silly trying to explain customer behaviour using only the data they have. At the end of the day, you have to work with the data you can access, but never underestimate the effectiveness of obtaining more (relevant) data.

5. Measuring the wrong thing

Maybe you recently read an article emphasising the importance of real metrics, like daily active users, as opposed to vanity metrics like number of signups to your service. You therefore decide to track the daily active users of your product. But have you thought about whether this metric is relevant to what you’re trying to achieve? If you run a business like Airbnb, where transactions are inherently infrequent, do you really care if people don’t regularly log in? You probably don’t, as long as they use the product when they actually need it. Measuring and trying to optimise the wrong thing can be very risky. Indeed, deciding on metrics and their measurement can be seen as the hardest parts of data science.

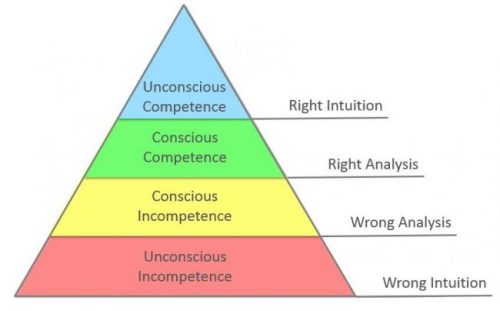

6. Not recognising your unconscious incompetence

To quote Bertrand Russell: “One of the painful things about our time is that those who feel certainty are stupid, and those with any imagination and understanding are filled with doubt and indecision.” Not recognising the extent of your ignorance when it comes to data is pretty common among those with no training in the field, which may lead to illusory superiority. This may be exacerbated by the fact that those who do know what they’re doing tend to talk a lot about uncertainty and how there are many things that are simply unknowable. My hope is that this short article would help people graduate from unconscious incompetence, where you don’t even recognise the importance of what you don’t know, to conscious incompetence, where you recognise the need to learn and rely on expert advice.

7. Ignoring expert advice

Once you’ve recognised your skill gaps, you may decide to hire a data scientist to help you get more value out of your data. However, despite the hype, data scientists are not magicians. In fact, because of the hype, the definition of data science is so diluted that some people say that the term itself has become useless. The truth is that dealing with data is hard, every organisation is somewhat different, and it takes time and commitment to get value out of data. The worst thing you can do is to hire an expensive expert to help you, and then ignore their advice when their findings are hard to digest. If you’re not ready to work with a data scientist, you might as well save yourself some money and remain in a state of blissful ignorance.

Note: This article is not a portrayal of how things are with my current employer, Car Next Door. Views expressed are my own. In fact, if you want to work at a place where expert advice is acted on and uncertainty is seen as something to be studied rather than ignored, we’re hiring!

Public comments are closed, but I love hearing from readers. Feel free to contact me with your thoughts.

Benoit Bernard

2016-08-22 15:26:34

Yanir Seroussi

2016-08-22 20:23:29

Sofiya

2016-08-30 06:43:22

Matthias Willerich

2016-08-31 09:05:01