Being a data scientist is a constant struggle with FOMO (fear of missing out): While you spend your time and attention on one tool, technique, or domain, dozens of other areas keep advancing at breakneck speed. It is impossible to keep up with everything. Fortunately, some advancements make it easy for a single person to accomplish tasks that previously required a team of experts. I covered some aspects of this phenomenon in a previous post: Software commodities are eating interesting data science work. Today’s post covers a specific case study, of how I recently overcame some of my deep learning FOMO by building a fish ID web app.

Background

Until October last year, I was working as a data scientist with Automattic. I was with the company for about 4.5 years in total. In my final two years, I was the tech lead for the company’s unified experimentation platform. In the two years prior to that, I co-led the implementation of the company’s machine learning pipeline. My interest in causal inference was one of the reasons I got involved with the unified experimentation platform, but this involvement meant I neglected my machine learning skills. Similarly, the machine learning pipeline I worked on was focused on marketing applications with tabular data. This meant that there was no need for me to do anything in computer vision or deep learning for many years. In fact, the last time I touched computer vision was due to deep learning FOMO, back in 2015.

Around the middle of last year, I helped mentor a local edition of the fast.ai Practical Deep Learning for Coders course. I figured it’d help me catch up on some recent developments, while helping others in the community. Given my hobby of volunteering as a scuba diver with the Reef Life Survey (RLS) project, it seemed like a good opportunity to do a side project around automated fish ID. However, the reality of full-time remote work meant that I had little motivation to spend extra time in front of the computer, so that side project never got off the ground.

Fortunately, I decided to leave Automattic and pursue work that better aligns with my values and interests. Rather than jumping into another full-time role, I decided to spend some time exploring and learning – a great antidote to the data science FOMO. First on the agenda after migrating my site off WordPress.com was making progress on the automated fish ID project. While it is still experimental, it’s now live on the RLS website, with the code available in my deep-fish repo.

The fish ID tool

As far as machine learning applications go, the tool I built isn’t groundbreaking – and that’s exactly the point. Many machine learning apps are boring and “uncool” (fulling fast.ai’s goal of making neural nets uncool again). But such apps are often useful. In my case, the tool scratches an itch felt by many RLS volunteers and other divers: Given a photo taken at a certain location, what fish is in the photo?

The tool relies on a classification model trained on images from the RLS website. In addition to the model, it lets users filter results based on previously-observed species at RLS sites. The following video demonstrates how it works:

I built the computer vision model with fast.ai, and the web app with Streamlit. It only took a couple of weeks to put everything together, and it could have easily been faster if I hadn’t taken the time to understand the underlying modelling code and tinker with various things. I’m sure that the model can be improved – my initial modelling attempts yielded a top-10 accuracy of about 60%, which I subsequently improved to about 72%. The main challenge is that there are 6,628 images and 2,167 species in the dataset I used, so it’s likely that some species can’t be identified reliably from the available training images.

You can read through my modelling experiments in the project’s notebooks. Copyright for the images belongs to the photographers, so I can’t share the full dataset.

Lessons learned

Rather than writing too much about the model and the code, which aren’t too unusual, I’d like to share a few lessons I learned while working on this project.

1. Getting reasonable performance out of a deep learning model can be cheap and easy. This lesson is highlighted in the introduction to the fast.ai course: With a few lines of code (and the right data), it’s easy to train reasonable models. It can also be cheap: I only used my laptop’s GPU for most of the experiments, and relied on Kaggle’s free notebook environment for experiments that I couldn’t run locally. On my dataset, I found that training a bigger (ResNet50) model with Kaggle didn’t improve accuracy in comparison to the smaller (ResNet18) model I could fit into my laptop’s GPU memory. This would definitely vary by dataset, but the point is that reasonable performance doesn’t necessarily require much human or computer work. In fact, much of the time I spent on modelling was for my own benefit, to better understand the material taught by fast.ai. Conceptually, I was pleased to discover that many things remained the same since my last foray into computer vision: Reasonable performance can be obtained by using established techniques and pre-trained architectures, while focusing on the data, the modelling pipeline, and augmentations. In my experience, this principle applies to many machine learning problems. This is summarised well by the directive from Google’s Rules of Machine Learning to “do machine learning like the great engineer you are, not like the great machine learning expert you aren’t.”

2. Building a Streamlit UI feels like magic. I’ve heard about Streamlit years ago, but this was my first time using it. I was impressed with how quickly I could put together a useful app using only Python. I went from a vague idea to a pretty complete implementation in a day (with some additional tinkering in subsequent days). It really is a game changer for data scientists.

3. Deploying a Streamlit app is a bit less magical. Streamlit Cloud seemed like a straightforward way to deploy Streamlit apps, but I ran into issues because I used a Conda environment. I managed to work around those issues, but it seems like the environment installed on Cloud isn’t truly isolated: Judging by the logs, Streamlit Cloud reads the Conda file and installs the required packages into an existing environment. This results in weird error messages that are hard to debug. I also ran into memory issues, which seem to be un-debuggable with the information provided by Streamlit Cloud. Still, I decided to initially deploy the app to Streamlit Cloud’s free tier and wrap it in an iframe for the RLS website. Given the steep increase in price from the free tier to the lowest paid tier (US$250 / month), it’s likely I’d switch to self-hosting if I run into more issues. This is a disappointing contrast to the magical experience of building the UI, but I hope that Streamlit Cloud would become easier to use with time.

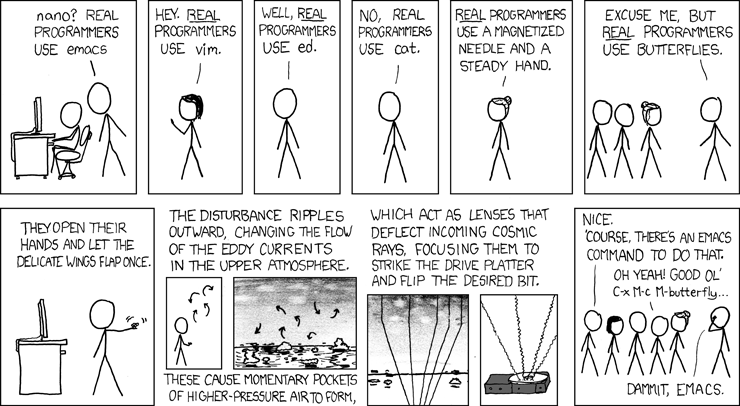

4. The fast.ai library is a great starting point, despite its quirks. Using fast.ai felt a bit like cheating, in the sense captured by xkcd’s Real Programmers comic. Given the hype, it feels like it should be harder to build useful models – real data scientists use PyTorch directly! But no, in reality it makes sense to use the best tool for the job. And there’s nothing wrong with something being easy or fast, as it lets you spend more time elsewhere. In the words of the principles behind the agile manifesto: “Simplicity – the art of maximizing the amount of work not done – is essential.”

Real Programmers don’t do easy things. Source: xkcd.

That said, the fast.ai library isn’t perfect. Debugging can be a bit frustrating, as it tries to do a lot of things automatically and mutates many objects in surprising ways. Its documentation is also somewhat lacking (perhaps due to the use of notebooks as the primary development environment), and its naming conventions can be a bit odd (especially the overuse of acronyms). But these are minor annoyances rather than blockers. It does work well for its main use cases, and it’s possible to go down to the PyTorch level when necessary.

5. As always, it’s all about the data and how you use it. This is hardly a new lesson for me, but it’s worth reiterating. Given the maturity of computer vision and other machine learning packages, data scientists should focus on getting relevant data and understanding the problem well. As Andrej Karpathy noted in his 2019 recipe for training neural nets, and I said in my 2014 Kaggle tips, you should aim to become one with the data.

6. FOMO will always be there, but it can be lessened. In general, I care more about making useful things than about using the latest techniques. This is why I prioritised working with RLS to get my tool deployed. Still, FOMO in data science is a well-documented phenomenon, and I suffer from it too. It’s encouraging that – given some free time and a clear head – it’s not that hard to catch up on recent developments. This is made especially easy by the availability of many free resources, like fast.ai. The main thing to remember is to focus on principles rather than worry about the million methods and tools that are out there – it was true in 1911, and it’s still true today.

Public comments are closed, but I love hearing from readers. Feel free to contact me with your thoughts.

Ishan Nangia

2023-06-14 10:51:18

Yanir Seroussi

2023-06-15 21:46:03