I was recently given a free eBook copy of the MEAP of Causal Machine Learning. MEAP stands for Manning Early Access Program, where books are published one chapter at a time. While the current version could use better copyediting and proofreading, I’m keen on reading more of the book as it becomes available.

Causal Machine Learning addresses a gap in the causal inference literature: While much has been published on the topic, putting the theory to practice in the real world can be challenging. For example, even though I considered Causal Inference: What If to be the most practical book I’ve read on the topic, I haven’t used much of its content directly. This is partly due to my focus on other areas, e.g., online experimentation and the energy space. But it is also due to the availability of sample code and mature packages that can be quickly adapted to my needs. The book aims to address the latter through a code-first approach that utilises Python packages such as Pyro, pgmpy, and DoWhy.

Despite the code-first promise, the book feels a bit slow at getting into the more exciting content. I couldn’t help but compare it to the fast.ai book, which first shows how to build and deploy a custom image classifier, and only then goes into unpacking how it all works. However, despite the verbosity of the first two chapters, by the third chapter things start to get more interesting. At the time of this writing, only chapters 1-3 are available, but upcoming chapters look promising based on the table of contents.

While lacking a production-ready example early in the book is a minor concern, I found the many grammatical errors more distracting. Even though a MEAP is essentially a draft, I think its proofreading level should be higher than that of a blog post.1 This is especially the case for paid content published by an organisation that cares enough to have contacted me to promote the book. As Steven Pinker says in the intro to The Sense of Style:

Style earns trust. If readers can see that a writer cares about consistency and accuracy in her prose, they will be reassured that the writer cares about those virtues in conduct they cannot see as easily. Here is how one technology executive explains why he rejects job applications filled with errors of grammar and punctuation: “If it takes someone more than 20 years to notice how to properly use it’s, then that’s not a learning curve I’m comfortable with.” And if that isn’t enough to get you to brush up your prose, consider the discovery of the dating site OkCupid that sloppy grammar and spelling in a profile are “huge turn-offs.” As one client said, “If you’re trying to date a woman, I don’t expect flowery Jane Austen prose. But aren’t you trying to put your best foot forward?”

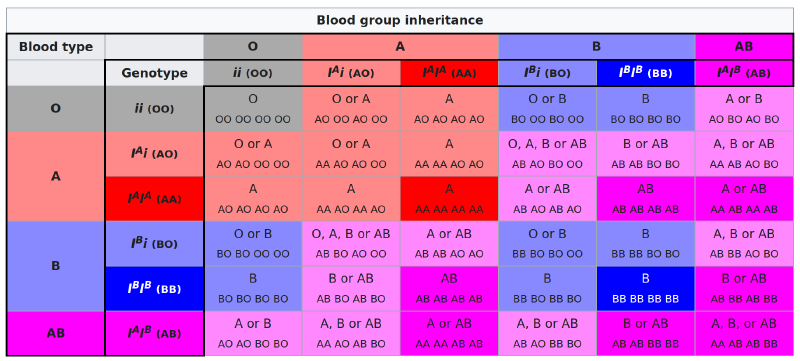

Another source of distraction is the choice of variables for some of the toy examples. For instance, one model of blood type inheritance confuses the phenotype and genotype, claiming that “knowing your grandfather’s [blood] type has no benefit in predicting your type once we know your father’s”. However, knowing the grandparents’ blood types can help predict the grandchild’s blood type even when the parent’s blood type is known. The toy example would work if it focused on genotypes, not on the common meaning of blood type as the phenotype (i.e., observable traits). See pages 58-60 in Probabilistic Graphical Models: Principles and Techniques for a less casual presentation of a similar example.

When observing parent phenotypes (ABO blood types) without genotypes, grandparent phenotypes are informative.

Source: Wikipedia – ABO blood group system (retrieved on 2022-09-11).

I also struggle with overly-casual statements like this one:

Suppose we were interested in modeling the relationship between altitude and temperature. The two are clearly correlated; the higher up you go, the colder it gets. However, you know temperature doesn’t cause altitude, otherwise heating the air within a city would cause the city to fly. Altitude is the cause, and temperature is the effect.

In fact, heating the air within a city would cause the heated air to rise. And extremely high heat can melt a city and the land it’s on, thereby causing a reduction in its altitude.

While this may seem like nitpicking, ill-defined causal graphs are a serious problem. One of my favourite papers on the topic is Does water kill? A call for less casual causal inferences, which argues that "[while] it is impossible to provide an absolutely precise definition of a version of treatment […] specification of versions of treatment is required only until no meaningful vagueness remains". However, “declaring a version of treatment sufficiently well-defined is a matter of agreement among experts based on the available substantive knowledge” because we don’t have an objective way of determining that treatments are well-defined. In line with this thinking, the book may benefit from reducing the variety of examples in favour of a handful of small datasets that are more well-defined and defensible.

Despite these shortcomings, I found chapters 1-3 of Causal Machine Learning pleasant enough to get through, and I look forward to reading more. Getting into DoWhy and other related packages has been on my list, and I’m sure I’ll learn a lot by following the MEAP. After tracking the field for almost a decade and complaining about the relative hype levels of deep learning and causal inference, it’s great to see a practical book that aims to marry the two. The Causal Revolution is truly upon us.

It is almost inevitable that when pointing out the mistakes of others I will make mistakes myself. I apologise for any mistakes and welcome feedback. ↩︎

's _steampunk painting of a data scientist reading a book about causal machine learning_.](https://yanirseroussi.com/2022/09/12/causal-machine-learning-book-draft-review/dall-e-a-steampunk-painting-of-a-data-scientist-reading-a-book-about-causal-machine-learning.png)

Public comments are closed, but I love hearing from readers. Feel free to contact me with your thoughts.