- If you're here for tips on CodeSignal's Industry Coding Framework, one of the best things you can read is their whitepaper on the topic. Scroll all the way down for a sample task.

- If you're searching for a remote job, you might find my list of established remote companies useful. You might also like Remote Rocketship for tens of thousands of job ads.

- If you're after a startup job, my Data-to-AI Health Check for Startups contains a set of questions you may find useful before accepting an offer.

- If you're here for a long rant about the silliness of hackable coding assessments and the hoops you need to jump through as a candidate, keep reading. Also feel free to contact me if you have a fun (or not so fun) story to share.

In the essay The Lesson to Unlearn, Paul Graham makes the claim that students are trained to win by hacking bad tests. That is, to get good grades, one has to avoid spending too much time on material that won’t be turned into test questions. Instead, one’s focus has to be on test-specific study. Students are taught that actual learning is less important than maximising grades. That is the lesson to unlearn.1

Even though the essay is a few years old, it’s been on my mind recently for two reasons. The first reason is that large language models are excelling in standardised tests: I’m impressed by this progress, but it’s also a reminder of the hackability of such tests and the need to employ critical thinking to stay ahead of the AI automation wave. The second reason is that I did a CodeSignal test myself, which led me to think more deeply on the hackability of automated and timed coding assessments. This post discusses my thoughts on the topic, using CodeSignal’s Industry Coding Framework as a case study. However, most of my observations should apply to similar tests.

What are hackable tests?

Hacking a test is different from cheating. Hacking entails following the test’s rules, but optimising your work to exploit its weaknesses and increase your score. It doesn’t necessarily entail changing the underlying properties that the test purports to measure. By contrast, cheating entails behaviours that are prohibited by the test’s rules, such as letting someone else do the test for you, or consulting resources that are defined as off limits.

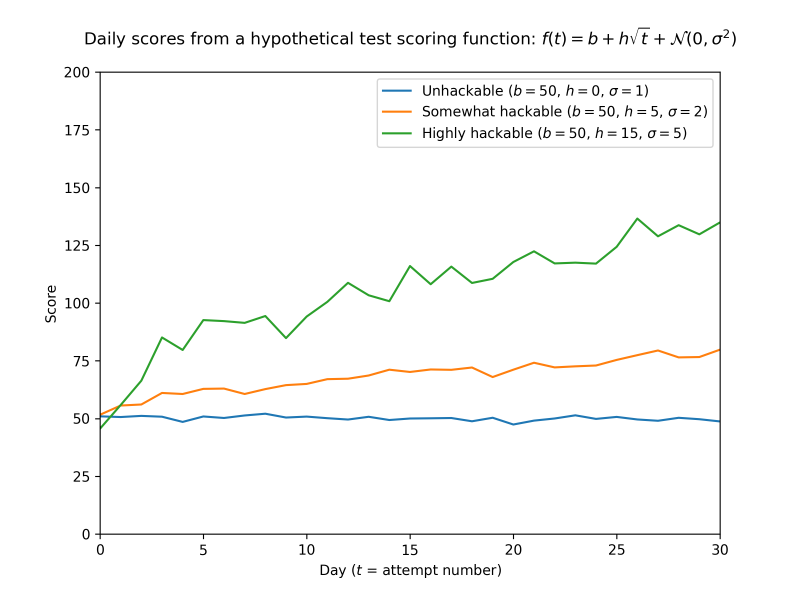

A test’s hackability isn’t a binary property. Hackability lies on a scale from unhackable to fully hackable, as demonstrated by the following examples and plot.

Say we take an adult and measure their height every day around the same time, over a period of a month. We can expect the measurements to have low variance. There’s little the test taker can do to significantly increase their height without cheating. The test is a good representation of the property it aims to measure – an unhackable test.

On the other end of the scale, say we take the same person and ask them the same set of questions over the course of a month. Our aim is to assess their skills in a subject area such as programming. Given that we’re repeating the same questions, they can find the answers and try to memorise them after each attempt. Assuming they’re sufficiently motivated, we can expect their scores to increase even if they know nothing about programming. This test is highly hackable. It’s hard to say that it accurately reflects the property it purports to measure, i.e., programming skills. This is because scores are strongly influenced by motivation to succeed in the test, as well as short-term memorisation and retrieval abilities.

An improvement over the unchanged test is generating variations from a set of possible questions.2 While our test taker would benefit from deeper skills in the subject area, they can also improve their scores by learning to recognise patterns in test questions, managing their time well, and memorising recurring elements. Again, we can expect their scores to improve over time and fail to accurately reflect the skills we care about. This gets us into the familiar territory of standardised testing, a category that I believe CodeSignal’s Industry Coding Assessments fall under. That is, tests that are not fully hackable, but still fall short of reflecting the properties they claim to measure.

Visualising hackable test scores as a function of time: f(t) = b + h * sqrt(t) + N(0, σ2). Starting from the same baseline b, scores increase with time t due to the hackability factor h that is multiplied by sqrt(t) (ability to improve decays with time). Each test attempt is affected by measurement noise, which comes from a normal distribution with mean zero and variance σ2. I assume that variance and hackability are positively correlated. While this function is made up and missing an upper bound, the shape of the curves should be about right. See notebook for source code.

Confessions of a test hacker

Before diving into the hackability of CodeSignal’s Industry Coding Framework, here’s a bit of background on my history as a test hacker.

Back in the day, I got pretty good at hacking tests. I enjoyed learning, but I also enjoyed getting high grades. This goes back to primary and high school and to my undergraduate degree in computer science – I graduated summa cum laude from a well-regarded university. My undergraduate days included hacks such as spending nearly all my waking hours solving past test questions during exam periods, as well as avoiding electives that had a reputation for being excessively time-consuming.

Similar test hacking skills were useful when interviewing with big tech companies. Early in my career, I worked with Intel, Qualcomm, and Google, and successfully interviewed with a few other tech companies. On a conceptual level, tech company tests weren’t that different from university tests, except that they were mostly oral (the dreaded whiteboard coding test), and could cover a wider breadth of topics. But even in 2005-2010, many questions leaked online, so I could follow the tried-and-tested hack of preparing by solving old test questions.

While I can do well in standardised timed tests, I never liked them. Despite being hackable, they are stressful, and maximising one’s score requires adequate preparation that is different from learning deeply about the subject matter. Perhaps the most absurd example of this was when I had to take an IELTS exam (a standardised English test) for the second time after completing my PhD, as part of my Australian permanent residency application.3 This was four years after taking the IELTS exam for the first time (in Israel). I spent the intervening years in Australia, authored peer-reviewed papers and a thesis, and gave multiple conference talks. There’s no doubt that my English skills improved over those years, and yet my second IELTS scores were lower.

Why were my second IELTS scores lower? Partly because I didn’t prepare for the speaking part of the exam, so I didn’t have much to say when the examiner asked me about my favourite colours and the favourite colours of my friends (yes, for real). I ended up paying the fee to contest the result, and it got bumped up to be closer to my pre-PhD scores. Still, this serves as a salient example of a hackable test. You can improve your IELTS score by getting better at doing IELTS exams, and without any change to your underlying English skills.

Once I became an Australian permanent resident, I had to do a driving test to convert my Israeli licence. This was also silly, as I was legally allowed to drive in Australia while I was on a student visa. Those years of driving weren’t enough to automatically convert my licence to the Australian system, so I was subjected to the driving test. While a bit stressful, it wasn’t too bad because driving tests are a close simulation of the skill they aim to measure – driving on streets and highways. As such, they’re not too hackable, though I was careful to signal my intent to the tester in a way that’s somewhat unnatural (e.g., braking and indicating earlier than necessary to avoid getting penalised). I had no issues passing the test.

Fortunately, I managed to avoid convoluted tests in the decade or so since that second IELTS exam. For job applications, I’ve mostly had my skills assessed through custom take-home assignments and paid trial work, e.g., in my long application process with Automattic and my last position with Orkestra, which started as a short-term contract. Those evaluations were less hackable than the whiteboard engineering questions of my early career, and therefore felt like a better reflection of the skills they were assessing.

On the hackability of CodeSignal’s Industry Coding Framework

Last week, I went through CodeSignal’s Industry Coding Assessment as part of a job application. While I agreed not to share the content of the assessment, there’s plenty I can discuss based on public information from CodeSignal’s website.

The whole experience felt like an unpleasant throwback to my old test hacking days in the noughties, but with a shinier user interface. While I’m rusty at standardised code tests, I did what any good test hacker would do: I started my preparation by searching for “Industry Coding Framework” on the web and on Blind, and reading through CodeSignal’s blog and resources. My initial search didn’t yield any unusual hacks, so I followed CodeSignal’s advice and did some of their practice questions. These turned out to be similar to the sort of questions I solved on whiteboards back in the day, except that these days, solutions are automatically scored in a web-based IDE.

Getting familiar with CodeSignal’s environment and refreshing my speed-solving abilities was definitely helpful when I took the real assessment, and that is a prime indicator of hackability. CodeSignal states that their Industry Coding Framework is designed to evaluate the programming skills of mid-to-senior engineers. These are skills that accrue over years and decades, much like English language skills. The ideal test for such skills shouldn’t be hackable, i.e., scores should be unaffected by repetition of similar tests over a short period. However, on the morning of the test I discovered that CodeSignal’s Industry Coding Assessments are hackable by design.

What I discovered was in a technical brief I initially overlooked, titled Industry Coding Skills Evaluation Framework (a longer version is stored in the Internet Archive). In the brief, they give the following breakdown of questions in their Industry Coding Assessments:

| Level | Expected time in minutes |

|---|---|

| 1 | 10-15 |

| 2 | 20-30 |

| 3 | 30-60 |

| 4 | 30-60 |

Adding up the time ranges gives us an estimate of 90-165 minutes to complete the assessment. But the time they give candidates to complete the test is… 90 minutes! In their own words:

The maximum allowed completion time for the assessment is 90 minutes; however, candidates are not necessarily expected to complete all tasks within this time limit. While longer assessments allow more accurate measurement of candidate skills, the willingness to complete assessments decreases dramatically for tests longer than 2 hours. Moreover, a major factor in assessing candidates’ skill levels is to see how far they can progress within the given time frame.

It makes sense that candidates don’t want to spend too much time on artificial tests. But a better approach would be to design a test that can be completed within the allotted time by skilled candidates who don’t engage in test hacking. Alternatively, they could allow more time and penalise candidates for going over the minimum of 90 minutes. This would make it easier to tell the difference between people who are slightly slower than the cut-off and those who are significantly slower. Implementation speed does matter in the real world, but it’s rarely measured on the order of minutes.

As it stands, my opinion is that making speed a key factor in test success makes it hackable because test-specific practice can lead to dramatically better results. CodeSignal’s decision to emphasise speed turns the test into a game like Speedcubing, and a game can be defined as the overcoming of unnecessary obstacles. Gamification may be in vogue, but I believe it’s better to keep it out of the job application process.

Further evidence for hackability comes from the fact that CodeSignal limits test attempts over varying time windows. If CodeSignal’s assessments were more like measuring one’s height or basic driving skills, this wouldn’t be needed. Further, this somewhat favours people who are in better assessment shape, e.g., because they’re applying to many jobs and are highly motivated to get them. Sadly, I found a thread on CodeSignal’s General Coding Assessment that says that the same CodeSignal results can be used by multiple companies, which means that people get locked out of opportunities for the time window that’s determined by CodeSignal. Anecdotally, while researching this post, I also discovered that many people dislike CodeSignal and have made similar observations to mine about the validity of their evaluations. Further, when it comes to General Coding Assessments, one can find many tips on test hacking (e.g., on Reddit and GitHub).

Another key issue is that the effective time given for the test isn’t 90 minutes. It’s typically two weeks from the time of notification, where one can’t see the test, plus 90 minutes to do the test. The two weeks can be used for extensive test hacking, depending on the test taker’s available time and motivation.

As both my available time and motivation were lacking, I didn’t use the full two weeks. I quickly lost interest in solving the same kind of questions I solved around 2005. I also suspected that some of the practice questions provided by CodeSignal had little relevance to the Industry Coding Framework. In addition, I read on Glassdoor and Blind that the company (a top AI lab) that asked me to take the test had ghosted some candidates after they had passed it, so I figured that maximising my test preparation time wasn’t worth it. With more than a week left before the deadline, I decided to take the test and move on.

Beyond hackability: Other issues with CodeSignal and automated assessments

To my surprise, when I clicked the Take Test button, I was given an option to do a demo test. Hiding the demo behind that button feels a bit unfair. I assume that candidates would click the button when they’re ready to take the test, not when they want to do further preparation. But I finished the demo test in 15 out of the allotted 60 minutes, so I felt good enough about it and moved on to the real thing.

Unfortunately, I ran out of time on the real test and scored 800 / 1000. According to the distribution in the archived version of CodeSignal’s Industry Coding Framework brief, this would have put me at the top 5% of test takers. But I’m not pleased with the result. The code I wrote was horrible and followed practices I’d never follow if I wasn’t trying to optimise for speed. There were also technical issues with the platform that got in my way: The IDE refreshed multiple times and claimed that I had lost connection, and having to use their IDE rather than a notebook environment is also a bit of a pain given the strict time constraints.

It’s likely I could have scored higher if I had maximised my test hacking efforts. Spending another week on preparation would have probably made a difference given that the hackability of the test is similar to that of an IELTS exam: Getting from zero to a perfect score is probably impossible over a short time span, but it is possible to nudge the score up by optimising the test-taking strategy and refreshing one’s bag of tricks (the sort of tricks that you don’t have to worry about retrieving quickly from memory under normal circumstances). For example, one relevant preparation step I could have followed was to attempt the sample questions from the Industry Coding Framework brief. I could have even taken it further and used ChatGPT (or another chatbot) to generate variations on the same theme. But as noted, I didn’t feel like it was worth maximising my hacking efforts given the circumstances.

Regardless of hackability, I believe that the test fails to capture many of the skills it purports to measure. Specifically:

- No points are given for good design without code that passes the automated tests. This is unlike more manual testing with a human assessor, where partial credit is given for having good ideas but running out of time.

- Not having to write any tests encourages lazy coding. Normally I’d think through edge cases, but optimising for the test score means that the only edge cases that matter are those that get caught by automated tests. It’s easier to deal with such issues if they get caught rather than spend precious time thinking about them. In real work, you need to spend time testing your code, which often requires more thinking than implementing the core logic.

- While CodeSignal claims that they test refactoring skills, the test design doesn’t even offer a caricature of real refactoring. In reality, new requirements are added over the course of days, weeks, months, and years – not minutes. And you need to refactor legacy code that runs in production and was written by many people of varying levels of proficiency and time pressures. This is nothing like tweaking throwaway code that you’ve written minutes ago.

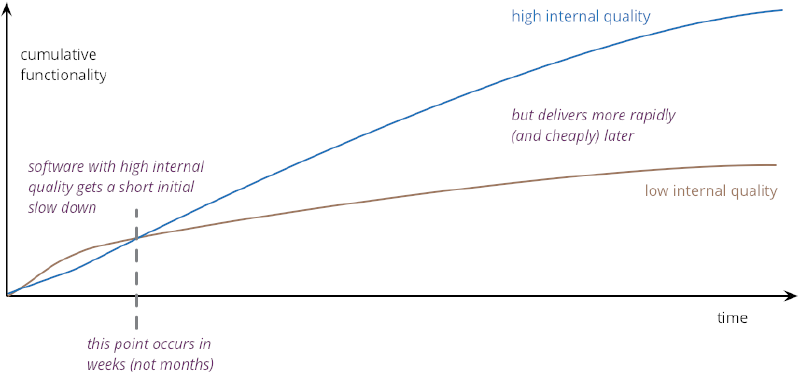

- Putting a high emphasis on implementation speed when aiming to test mid-to-senior developers disadvantages those who have gotten into the habit of avoiding software engineering classic mistakes such as shortchanged quality assurance and code-like-hell programming.4 As noted by Martin Fowler, ignoring internal quality increases the pace of feature delivery early in a project’s life, but slows it down in the longer term (within weeks). Setting a 90-minute time limit on a test that’s supposed to take a minimum of 90 minutes may filter out experienced engineers who have developed good habits and didn’t bother unlearning them for test hacking purposes. This is an instance of the McNamara fallacy – time is easy to measure, but deep skills and good habits aren’t. Unfortunately, CodeSignal is heavily biased towards that which is easy to measure, but rather than admitting these flaws, they make unsupported claims about the effectiveness of their measurement approach (just read the archived version of the brief for a bit of a laugh).

Hacking timed tests can be at odds with habits that are needed to develop high-quality feature-rich software. Source: Martin Fowler’s Is High Quality Software Worth the Cost?

Closing thoughts: Partial hackability doesn’t imply complete uselessness

Hackability is a non-binary measurement. Even hackable tests can be reflective of the properties they’re supposed to measure. As CodeSignal says in their marketing materials, they offer a cost-effective approach to filtering out candidates, at least when compared to manual in-house recruitment. From a hiring perspective, cheap filters are valuable when a company is flooded with qualified candidates, even if such filters have a high false negative rate. The goal is achieved as long as the filter also decreases the false positive rate. Favouring test hackers is a small price to pay for an initial filter – even if you get candidates to optimise for the wrong metrics, this can be corrected with more thoughtful testing down the track. However, turning the application process into a series of games risks alienating some candidates, who won’t bother applying even if they can do the job well.

Among other factors, test scores are a function of the test taker’s skills, test design/hackability, and the test taker’s preparation for the specific test.5 I believe that take-home coding assessments and real-work simulations offer a better candidate experience and provide a better signal to companies than artificial time-limited tests like CodeSignal’s Industry Coding Assessments. This is supported by statements from CodeSignal: The brief discussed above explicitly says that “longer assessments allow more accurate measurement of candidate skills”, and they found in their 2023 survey that candidates prefer take-home coding challenges to CodeSignal assessments.6

My hope is that this post would help future users of automated coding assessments in general, and CodeSignal’s Industry Coding Framework in particular. Perhaps it’d also nudge CodeSignal to improve their platform. They can do better. I won’t be holding my breath, though – standardised assessments like CodeSignal and IELTS are a part of a massive industry. There’s little incentive for incumbents to change their ways, but it is possible that large language models excelling in test hacking would force their hand.

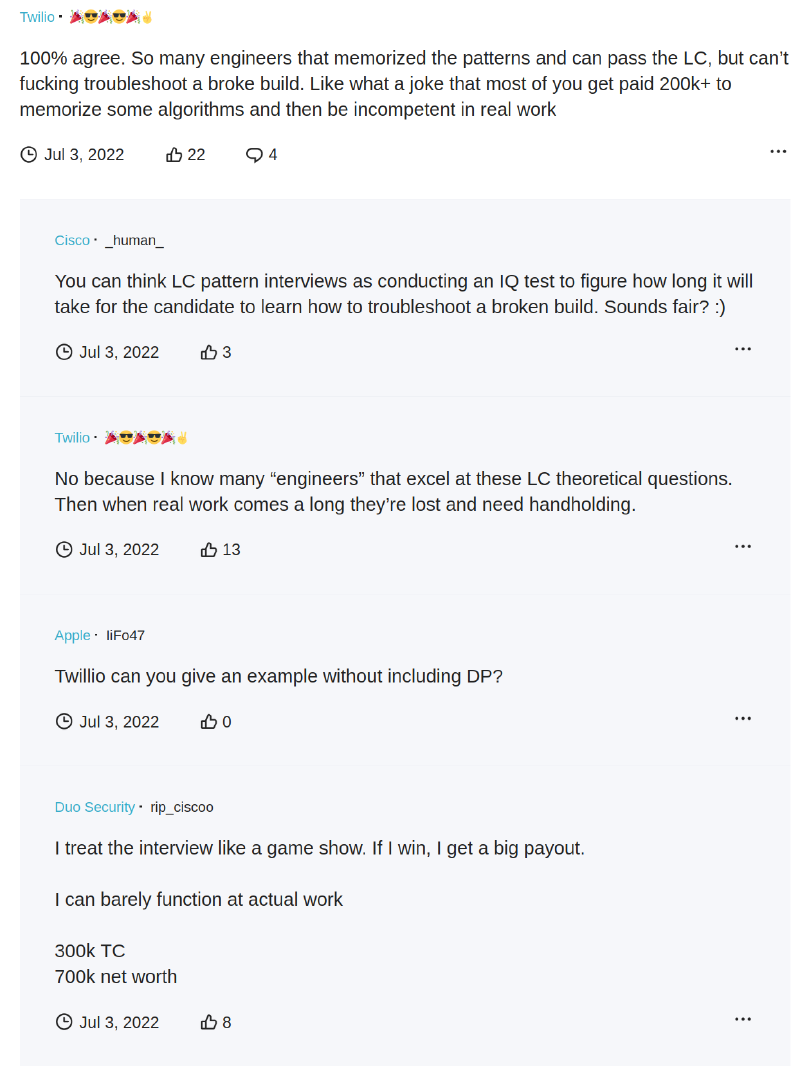

Some comments from a Blind thread on coding assessments. Seeing it all as a somewhat-useful game is probably the way to go.

Note: I reached out to CodeSignal for a comment on this post, but haven’t heard back after more than a week.

As with many Paul Graham essays, I find myself in agreement with some of his ideas and disagreement with others. But hackable tests are definitely a thing, e.g., see teaching to the test and Campbell’s law. ↩︎

Taking a machine learning analogy, asking the same questions repeatedly is likely to lead to overfitting. Drawing new questions from the same distribution is akin to adding a validation set, while dealing with the sort of problems encountered outside standardised tests is indicative of the generalisation error of the test taker. ↩︎

It says a lot about the hackability of higher education that the Australian government requires a PhD graduate from a top Australian university to prove that their English skills haven’t deteriorated after four years in Australia. Similarly, companies that look at educational pedigree but put recent graduates through their own set of tests implicitly distrust the grades given by universities. ↩︎

The only time you’re likely to face ridiculous time pressures that are measured in minutes is when something breaks in production. Production issues can be minimised through investment in solid processes and quality over a project’s lifetime. That is, you go slow to go fast and avoid fire-fighting. Take-home exams and real-work simulations are more reflective of the sort of thinking that’s required from senior engineers because good ideas often manifest when you take the time to design a system and avoid jumping into code-like-hell mode. Going with the first thing that comes to mind is a habit that’s better left to chatbots. ↩︎

Preparation is partly a function of motivation to pass the test, which is a positive indicator despite being unrelated to possessing the skills the test purports to measure. In my case, motivation to maximise the score was lacking, so the company got useful information out of my imperfect score. Why was my motivation lacking? Because the role seemed interesting enough to apply to, but not worth working too hard to get. The opportunity cost of neglecting my other endeavours in favour of test hacking seemed too high. ↩︎

See page 11 of the linked survey. Like other materials from CodeSignal, it’s somewhat comical. They state that “candidates view CodeSignal assessments more favorably than timed coding assessments in general (p = 0.034)”, but looking at the table, the mean score given to CodeSignal assessments is 3.41 / 5, while general timed coding assessments were given a mean score of 3.37. That is, a difference of 0.04 – it’s hard to call this practically significant, despite the p-value. Could it be that CodeSignal’s IO psychologists missed the many memos on p-value pitfalls, such as the one by the American Statistical Association? In any case, if they consider the 0.04 difference to be notable, why do they say nothing about the 0.06 difference in favour of take-home coding assignments or the 0.17 difference in favour of coding interviews? Personally, I’d also report the full distribution rather than just the means. It’s easy enough to visualise a five-point scale. ↩︎

Public comments are closed, but I love hearing from readers. Feel free to contact me with your thoughts.