I’ve been volunteering with the Reef Life Survey (RLS) citizen science project since 2015. RLS volunteers follow the same underwater visual census methodology that has been in use for decades, thereby producing data series that help inform the management of marine ecosystems. In simpler terms, we count fish (and some invertebrates), and this helps various organisations know what’s happening underwater. Among other places, RLS data has been used in scientific publications in Nature and elsewhere, and to inform the management of Australian marine parks.

Over the years, I created a few online tools to help volunteers with survey work. These included web apps to visualise survey results and study species, as well as infer species from underwater photos. More recently, I agreed to help with the general maintenance of the non-WordPress parts of the RLS website and backend (somewhat reluctantly, but I suppose that’s what happens when you do things out of love).

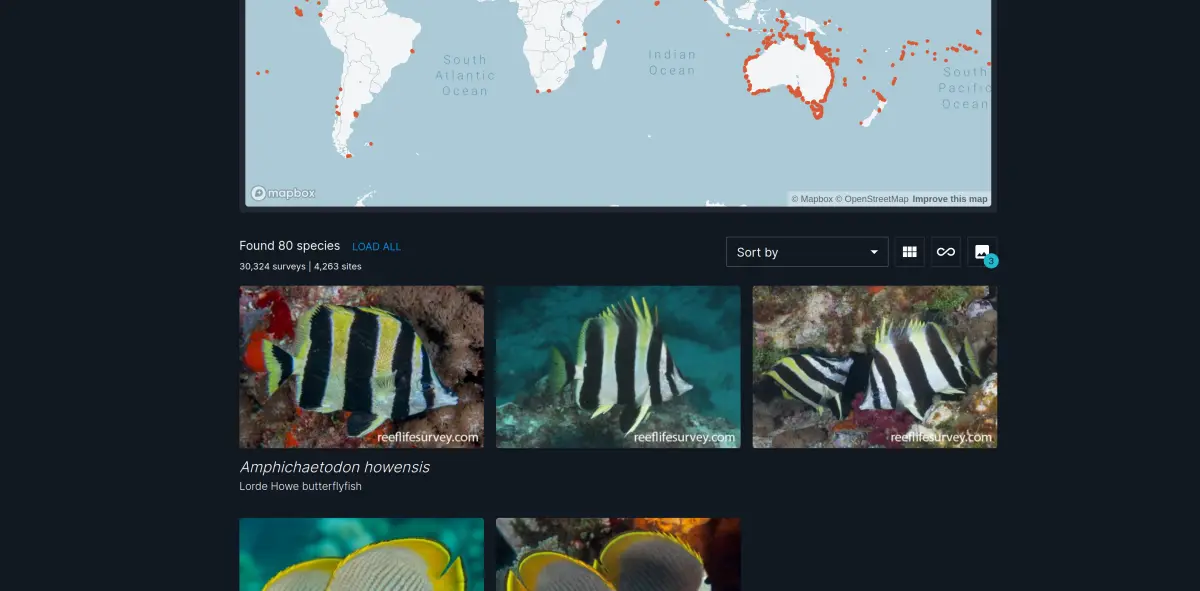

Taking greater responsibility to help the tech side of RLS along with an alignment of the research grant stars led to an opportunity to revamp the Reef Species of the World (RSoW) section – a collection of over 5,000 species with in-situ photos, descriptions, and empirical distributions derived from RLS surveys. My focus in this project was on product management, data pipelines, and backend work. I was joined by my brother, Uri Seroussi, who was in charge of front-end development (which became much more substantial than in the original RSoW).

The original RSoW was a traditional PHP application that relied on a MySQL database to serve requests, with most of the HTML constructed on the server. By contrast, we re-architected the new RSoW as a progressive web app using Next.js, which has the following advantages and new features:

- Fully static site: served faster with reduced server load.

- Faster search and navigation: happens on the front-end without round-trips to the server.

- Installable app with offline availability: RSoW can now be installed as a mobile or desktop app, and run without an internet connection.

- Client-side image classification: offline availability includes image classification in the browser, which is useful when surveying in remote areas.

- Replacement of previous tools and pipelines: providing a more consistent user experience and improved data reliability.

The rest of this post provides details on the architecture and implementation of the new RSoW and its underlying data and machine learning pipelines. But the best way of getting a feel for the data and the tools is to have a play yourself.

The new RSoW architecture diagram reflects the compromises between rebuilding and retaining legacy systems

The RSoW web app

We didn’t start with a blank slate: RSoW was already a public website, with many individual species pages ranking well on web searches (the main source of traffic). As such, a guiding principle was to retain as much of the original functionality as possible, and then build new features on top of it.

When approaching a legacy codebase, there’s always the question of whether rebuilding parts or all of it is a worthwhile endeavour. As Jason Cohen notes, a more apt name for “legacy code” is “revenue code”, i.e., the code that embodies all the original and changed requirements, and has withstood the test of time. Even though RLS’s code isn’t meant to generate revenue, it’s always easy to mess things up when re-implementing existing functionality.

The main reasons we decided on a rewrite of the front-end were:

- User experience: Speed things up, as some species searches were pretty slow due to server round-trips and inefficient database queries.

- Extensibility: Make it easier to add new features.

- Offline availability: This is impossible with a traditional PHP back-end, but feasible if all the data and code gets shipped to the client.

We chose Next.js as the front-end framework since it’s well-established and supports static exports. Parts of the RLS website run on WordPress, so it’s easy to add statically-generated pages and serve them efficiently via Cloudflare (I wasn’t keen on complicating the stack by adding a Node backend). With static exports, we regenerate all the species pages whenever the data changes, which means that end-user page requests don’t need to touch the database. In addition, the main search page downloads three JSONs with all the data it needs to perform any species search (see sites.json, species.json, and surveys.json in the rls-data repo). Minified and compressed, these JSONs add up to less than 2MB of data, which isn’t tiny, but it is a small price to pay to avoid hitting the database. The JSONs also cache well on Cloudflare, like the rest of the web app’s files.

From a user perspective, replicating the original functionality was the less exciting part of the project. Faster and less buggy code is obviously better, but once feature parity was achieved, we turned our attention to some new features:

- Supporting offline availability and installation by turning RSoW into a progressive web app: On its face, this was supposed to be simple given the

next-pwapackage, but it turned out to be a bit tricky because the original package was abandoned, and due to multiple layers of caching. It’s well-known that cache invalidation is one of the two hard problems in computer science (along with naming things and off-by-one errors), and progressive web apps offer a lovely variety of caches to deal with – everything needs to be cached on the client for offline availability. We got there after some tinkering and dealing with head-scratching bugs, some of which were caused by other caching layers in addition to the client-side caches (including Cloudflare and some misconfiguration of an early version of the app). - Knowledge test: A separate grant came along and Uri had the opportunity to extend RSoW by adding a section that helps test new volunteers ahead of them joining RLS.

- Species frequency exploration: Bringing in the full functionality from the first tool I built for RLS back in 2017.

- Client-side image classification: Deprecating the Streamlit app I built a couple of years ago.

Data and machine learning pipelines

On the back-end, there was an opportunity to simplify things by retiring the original PHP code that processed survey data in favour of the pipelines I implemented in the rls-data repo. Ultimately, survey data comes from the Australian Ocean Data Network (AODN), which holds many more datasets in addition to RLS. Originally, the PHP code that processed survey data into the MySQL database evolved separately from rls-data, which I implemented to generate JSONs for the tools I built. As rls-data is an open source project and the raw survey data is relatively small (<1GB), it made sense to process it with a daily GitHub Action (GHA) script that runs for free. The resultant JSONs are committed to the repo, which means that any unexpected changes are easily tracked (I keep an eye on the commits). It was simple to expand the existing rls-data pipelines to generate all the JSONs needed to serve RSoW, and then say goodbye to the PHP code that implemented similar functionality.

I’m aware that running data pipelines with GitHub Actions isn’t going to win any awards for sophistication, but it’s a great fit for this project. The key principle is to use the right tool for the job, not the shiniest tool.

One part of the original RSoW that we barely touched was the management interface, which allows RLS admins to update species data and upload pictures. The gains from replacing the admin part of RSoW would have been negligible, so it still runs the old PHP code on top of MySQL. Unfortunately, this meant I couldn’t retire all the PHP data pipelines, as species data also comes from the Australian Ocean Data Network and is joined with the edits made by RLS admins. This exemplifies the pragmatism that one often needs to apply when faced with legacy revenue systems: If a system works and there’s no real benefit to replacing it, sticking with the old system is the right thing to do (even if it makes your architecture diagram more complicated).

I have big plans to improve the machine learning model for inferring RLS species from user images, but it’s somehow never a priority. For RSoW, I did make it a priority to support serving the model with a simple API, but then I decided it’d be worth the effort to export it to ONNX for client-side image classification. This was partly driven by curiosity about ONNX, but it also had two key benefits: (1) support for offline classification; and (2) simplified & cheaper serving architecture, as ONNX models can be served from S3 and don’t require RLS to pay for server-side compute.

As to the machine learning pipelines, they all need to be manually triggered, which is fine since the image data changes slowly. These pipelines are implemented in notebooks and the command-line interface of the ichthywhat repo. I have a bit of a dream of this being an early precursor to complete automation of RLS data collection, with the historical RLS data series continued by divers who would mostly serve as video takers and fish scarers (using cameras without human divers would lead to different biases in the data). However, this is a big project that is probably best left to my next PhD, i.e., it may never happen.

In the meantime, I hope to continue diving with RLS, and aim to make pragmatic decisions to keep RSoW running and supporting the community.

Public comments are closed, but I love hearing from readers. Feel free to contact me with your thoughts.