In my post on your startup’s first data hire, I noted in passing that the hire’s initial role would be setting up the company’s minimum viable data stack. But what exactly is that?

Conceptually, a minimum viable data stack follows the same principles as a minimum viable product. Breaking it up, it is:

- Minimal: You don’t want to over-build beyond your resources. Instead, set up the simplest stack that satisfies the startup’s near-term needs. Then iterate based on feedback and new requirements.

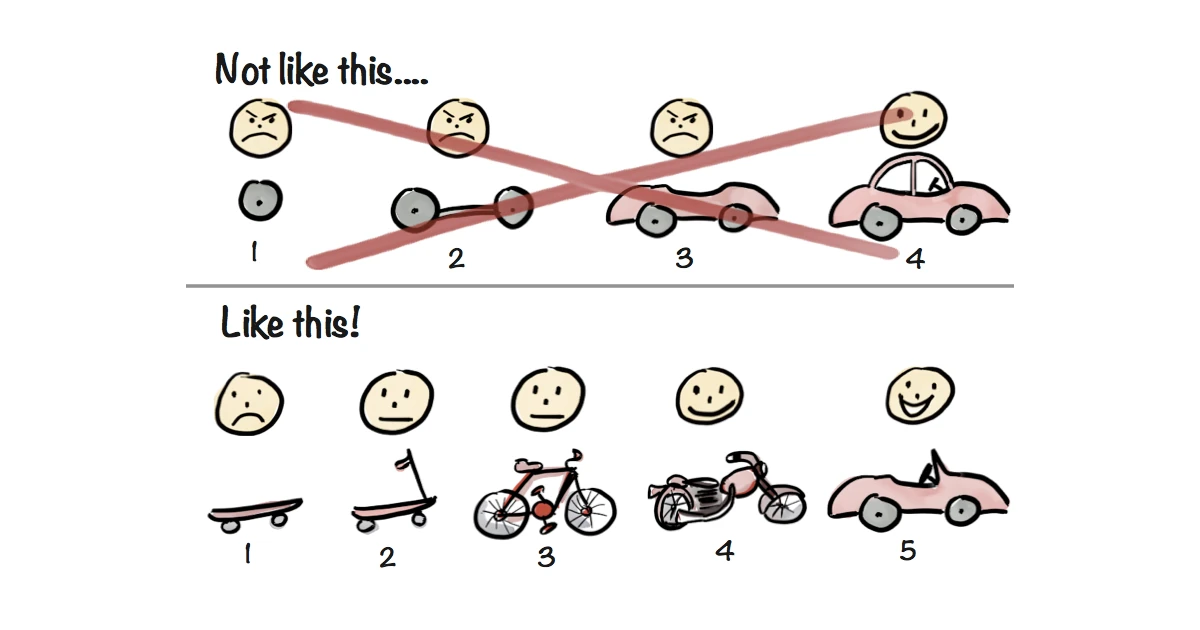

- Viable: While this is sometimes forgotten in favour of an over-emphasis on minimality, your data stack has to be viable. That is, it has to satisfy stakeholder needs through every iteration, as shown by the classic drawing above.

- Data Stack: This is the product that’s getting shipped and built iteratively, consisting of the components listed below. As in my previous post, I’m assuming a startup where the data stack initially serves internal stakeholders. The main difference between a consumer-facing product and an internal-facing data stack is that the latter has users you can easily talk to and fewer unknowns. This makes the task of satisfying user needs easier.

This post is the first in a series that will serve as a quick reference for those embarking on the journey of setting up a minimum viable data stack. Future posts will go deeper into each of the key components. However, I can only cover limited ground – readers are encouraged to consult books such as Fundamentals of Data Engineering for a more thorough treatment of the topics covered in the series.

Components of a minimum viable data stack

As we’re talking about a minimum viable data stack, this list of components isn’t exhaustive. The components I consider to be the bare minimum are:

- Storage: Where the data lives.

- Ingestion: How the data makes it into storage.

- Transformation: The layer that joins and changes raw data into more useful form.

- Analytics: Presentation layer, which can be consumed by non-technical stakeholders.

Components that are perhaps conspicuous in their absence are: machine learning / AI (higher on data’s hierarchy of needs – I assume this will come later), data serving / querying (implicitly included in other layers), and orchestration (also implicit – I assume dependencies are initially simple enough so that any orchestration approach would work).

Considerations beyond stack components

There are at least two critical items to think of early on. I consider a data stack to be nonviable if no thought is given to:

- Security. Ignore data security at your own peril. Examples abound of serious data breaches, which are often the result of trivial mistakes or poor design decisions. Starting off by implementing security checklists and following best practices like the principle of least privilege is way easier than trying to enforce them later on. A good technical read on the topic is Building Secure and Reliable Systems, though you’d need to cherry-pick principles to match your needs (it’s a book by Google, and your startup is not Google).

- Privacy. You should be aware of compliance requirements for the data you store, especially when it comes to private and sensitive data. As with security, it’s much easier to start by complying with privacy requirements than retrofitting a stack once stakeholders have come to depend on data that shouldn’t be collected or retained. In the spirit of minimality, it’s best to err on the side of not storing sensitive data when it isn’t required. This also helps minimise the potential effect of breaches.

Other key considerations include:

- Data generation. I assume that the business is generating data from multiple sources, which need to be ingested into a single storage system to ultimately drive decisions. If there’s only one source system, it may be too early for a data hire, or for a more sophisticated data stack. When considering data sources, it’s important to keep in mind the three Vs of data: Volume, Velocity, and Variety.

- Quality assurance. It’s important to have some automated checks in place to avoid breaking pipelines and maintain high data quality before making changes to production systems (e.g., changing transformation or ingestion code). Again, it’s easier to start with high standards for quality than enforce them retrospectively. Low quality is likely to result in low trust of any data or insights, making the stack nonviable.

- Observability/monitoring/incident response. Inevitably, things will break in production. With good observability and incident response practices, the data team will proactively address such issues – ideally before any stakeholders notice. This goes hand in hand with setting high quality standards – the sort of culture that is easier to set early on than change down the track.

- Data management. There are many items that fall under data management (e.g., see the list on Wikipedia). Many of them are addressed implicitly or not addressed at the early stages of a data stack. For example, data discovery isn’t a major issue when the data team consists of a single person. Still, it’s worth being aware of management considerations that arise as the data stack matures.

- Timely automation. As a broad generalisation, engineers like automation. Erring on the side of automation is often a good idea, as it lets computers do what they do best and frees up human time to deal with things that have to be done manually. Done right, automation increases overall quality. However, creating automations takes time, e.g., if a monthly report takes five minutes to generate, and it’d take a day of coding to automate, it’s probably enough to write up the procedure to generate it. You have bigger fish to fry.

- The need to be boring. Another trap that you can easily fall into is trying shiny new tools. Despite what vendors might say, it’s rare for new tools to be truly transformative. You should strive to be boring in your choice of components. Use proven tools and services for the minimum viable data stack, keeping the shiny experimental stuff to your hobby side projects (I learnt this the hard way).

- Speed of iteration. Some people believe that high quality always comes at the cost of iteration speed. I disagree, for the same reasons Martin Fowler pointed out in an essay on how increasing the internal quality of software increases iteration speed within weeks of the start of a project. In short, if you don’t invest in quality, you’re committing yourself to spending much of your time firefighting as the complexity of the data stack increases. However, overthinking reversible decisions or spending too much time on non-critical issues is also a real possibility. Above all, you must remember that the goal of the data stack is to support business decisions, which may require some compromises to deliver value as rapidly as possible.

Next: Choosing components

As noted, I’m aiming for this to be the first in a series of posts on setting up a minimum viable data stack. Each future post will be dedicated to each of the key components, going deeper into currently-available tools for storage, ingestion, transformation, and analytics. The focus will be on tools that are sensible to use by startups.

Stay tuned for future posts! In the meantime, feedback is always welcome.

Update 2024-08-19: I eventually gave up on the series – here’s why.

Public comments are closed, but I love hearing from readers. Feel free to contact me with your thoughts.