One of my challenges with the transition to consulting is running effective diagnoses. As a long-term employee, you develop an awareness of problems within your organisation – especially problems you’ve caused yourself (e.g., by taking on tech debt). As an outsider with deep industry knowledge, you can guess what the problems are based on the initial brief. However, there’s often no way around spending time with a client to thoroughly diagnose their problems and propose custom solutions.

For a recent engagement, the high-level brief was to help the client overcome challenges around the reproducibility and rigour of their machine learning work (AI/ML henceforth). Without getting into confidential details, it was immediately apparent that some of the challenges were due to a lack of engineering experience by the scientists building the models (which is a common problem).

As my path into data science & AI/ML was via software engineering, I’ve always found myself doing engineering work in my data roles. If I were a full-time employee of the client, I’d have ample time to introduce engineering best practices and processes, and help the scientists develop relevant skills (e.g., as I’ve done in my full-time work with Automattic). However, as an external consultant, I didn’t have the luxury of understanding the context and building relationships over months and years. While I do offer long-term engagements to help with implementation, I prefer completing the initial discovery phase as a separate engagement, before requiring either party to commit to working together long-term. Therefore, I had to figure out an effective way to diagnose the problems and propose a roadmap.

As a part of the discovery phase, I could use the questions from the Tech section of my Data-to-AI Health Check for Startups. Specifically, the first three questions should provide a good overview of the current state of processes and tooling:

- Q1: Provide an architecture diagram for your tech systems (product and data stacks), including first-party and third-party tools and databases. If a diagram doesn’t exist, an ad hoc drawing would work as well.

- Q2: Zooming in on data stacks, what tools and pipelines do you use for the data engineering lifecycles (generation, storage, ingestion, transformation, and serving), and downstream uses (analytics, AI/ML, and reverse ETL)?

- Q3: Zooming in further on the downstream uses of analytics and AI/ML, what systems, processes, and tools do you use to manage their lifecycles (discovery, data preparation, model engineering, deployment, monitoring, and maintenance)? Give specific project examples.

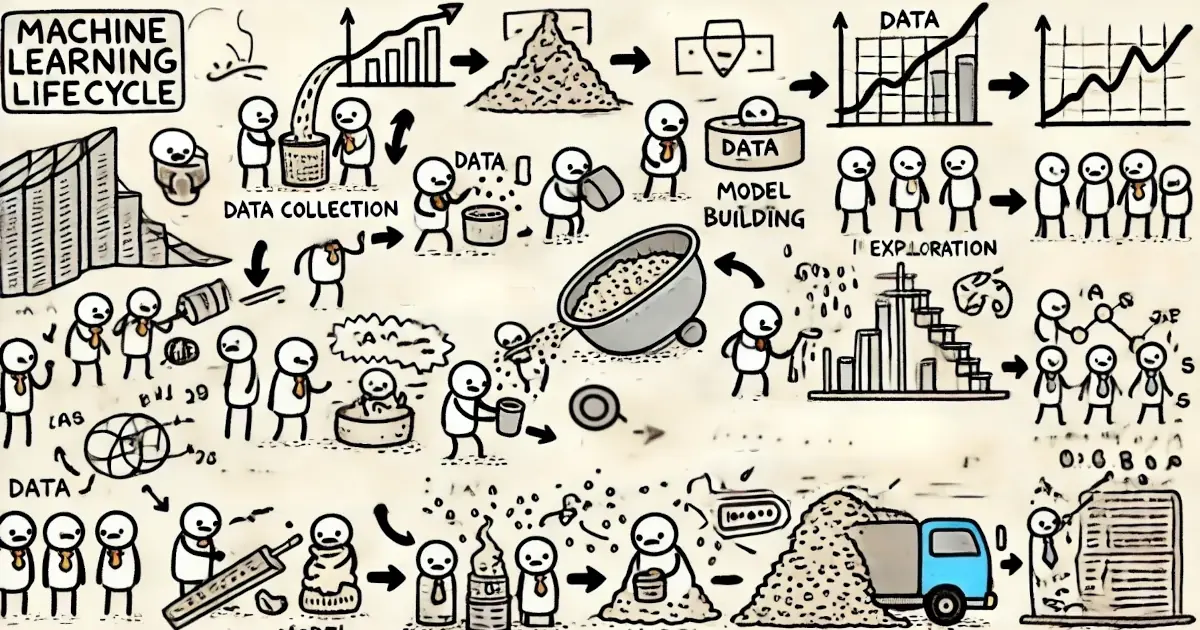

However, while I was satisfied with the definition of the data engineering lifecycle (as noted in the Q2 link, its ultimate source is the book Fundamentals of Data Engineering), I didn’t love the definition of the AI/ML lifecycle. As I find lifecycle models incredibly useful for uncovering gaps and opportunities, I decided to dig deeper and find an AI/ML lifecycle model that suits my diagnostic needs. The rest of this post discusses the problem in more detail, and presents my findings.

My problems with the AI/ML lifecycle model

The AI/ML lifecycle model is messy in at least three ways.

First, the subject of each stage is different:

- Discovery deals with the business context, stakeholders, and technical feasibility.

- Data preparation focuses on transforming and exploring the data.

- Model engineering is where AI-assisted humans create models via iterative coding and experimentation, with the goal of satisfying offline metrics.

- Deployment, monitoring, and maintenance happen in production – potentially by different people and with results that are far removed from the expectations set by offline metrics.

Contrast this with the relative simplicity of the data engineering lifecycle: generation, storage, ingestion, transformation, and serving are all things that happen to data. That is, data is the subject of each stage.

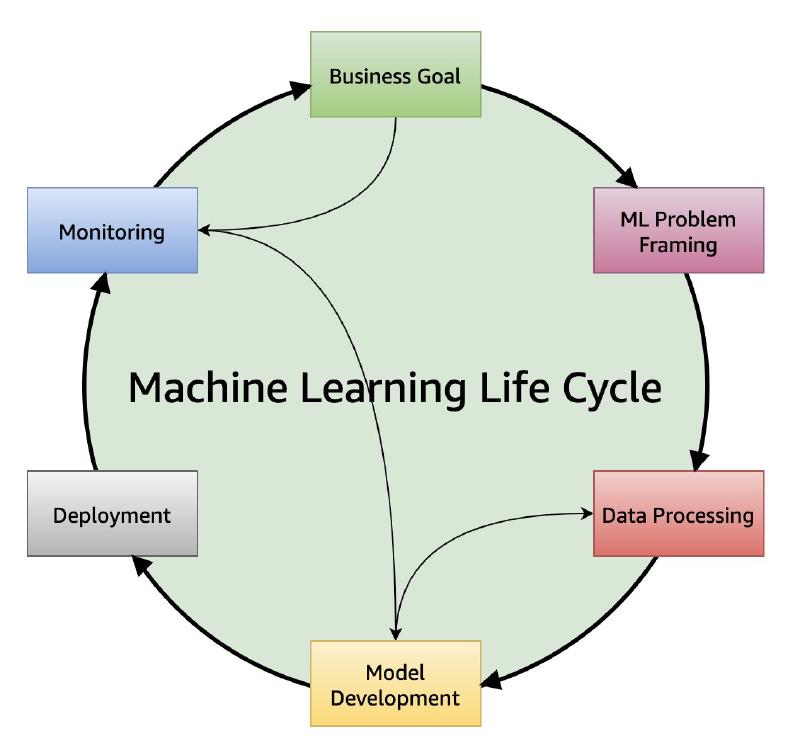

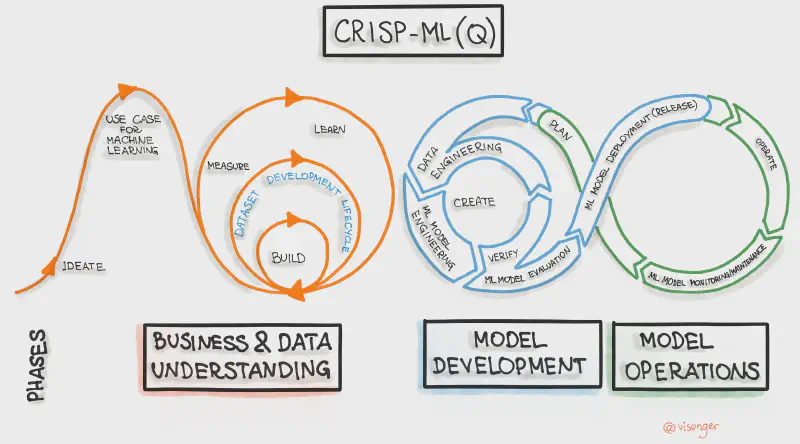

Second, experimentation and the probabilistic nature of AI/ML lead to feedback loops. Authors of AI/ML lifecycle models attempt to capture these loops in diagrams that I find confusing. For example, see two of the better sources I found:

Third, human analysis & experimentation require different mindsets and tools than productionisation. If you’ve ever worked with AI/ML, you’d know that to be effective you need to step back from optimising for what’s going to happen in production – even if you’re trying to improve a production model. This is partly why notebooks are so popular with data scientists – they support fast iteration. However, notebooks are inherently messy, which is why they aren’t great for production use. This is despite the existence of tools like nbdev and production notebook support by major data platforms and big tech players.

With my background in both software engineering and data science, I have used notebooks extensively for rapid experimentation. But I don’t want notebooks in production, where the goal is to maintain a well-structured codebase with testable components and reproducible flows.

Integrating analysis into the AI/ML lifecycle model

The ideal lifecycle scenario is captured by this quote by David Johnston (from the article on notebooks in production cited above):

Notebooks are useful tools for interactive data exploration which is the dominant activity of a data scientist working on the early phase of a new project or exploring a new technique. But once an approach has been settled on, the focus needs to shift to building a structured codebase around this approach while retaining some ability to experiment. The key is to build the ability to experiment into the pipeline itself.

Unfortunately, reality is often far from this ideal, as noted by Jason Corso (emphasis mine):

This rose-tinted view of the machine learning process is often called the machine learning pipeline. And, well, I’m done with hearing about the machine learning pipeline. Everyday work in real machine learning could not be farther from a pipeline.

[…]

As a professor and a founder of an artificial intelligence startup, I’ve had the luxury of interacting with literally hundreds of ML teams. In nearly every case, I’ve heard about the process of going back to the drawing board for the label space, or the inadequacy of the evaluation data set in terms of measuring production performance, or some other issue. It seems the machine learning process is much more complicated than we thought, and certainly much more complicated than we’d like. And, surprisingly, it seems to rarely involve the model choice or the implementation.

[…]

I liken the real machine learning process to a random walk. The machine learning problem is often fairly well-designed. And, we take a random walk through some complex space defined by a cross-product between possible datasets and models. It’s a massive and complicated space that evades a careful definition. But, at any instant, we are at a point in that space. As we modify a dataset or a model (architecture or parameters), we move through that space. With the elusive definition of the space, it is impossible to measure a “gradient” of our work in a principled manner.

[…]

Analysis is hence at the heart of the machine learning random walk. The more one can reduce the uncertainty around each decision — each jaunt through the space — the faster one can navigate the random walk toward a performant system.

[…]

Optimizing the machine learning process requires an appreciation for the high levels of uncertainty present. Whereas classical computational thinking may lead one to infrastructure-focused orientation that emphasizes the speed and effectiveness by which data gets processed, optimizing the machine learning work instead requires effective mechanisms to uncover false assumptions, mistakes and other mishaps in the manner in which the problem statement was rendered into a computational system.

I imagine it seems natural to think: ok, fine, once this uncertainty is managed and we have a deployable model, then we can set up our fast, automated pipelines and crunch away in production. To this thought, I’d answer a very clear “maybe.” Sure, one wants to optimize and automate. It certainly makes sense. But, I would still exercise caution: data drift and evolving production expectations create a need to constantly measure and evolve these machine learning systems.

In all of these situations, clear software-enabled analytical decisions are required to optimize the machine learning random walk.

The full article is worth reading – it was hard to choose just the above quotes!

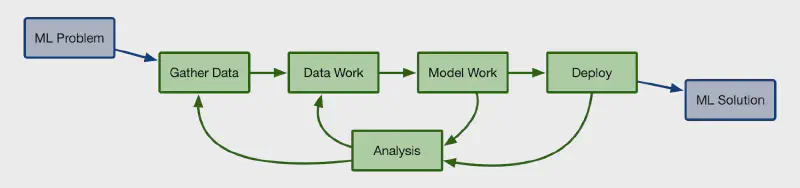

Following the introduction of analysis as an essential part of AI/ML work at any stage, Corso proposes a simple pipeline diagram that allows for loops via analysis:

I like the simplicity of the diagram, but it’s missing some arrows. For example, sometimes the ML Problem needs redefining, and sometimes analysing the data can lead back to data gathering.

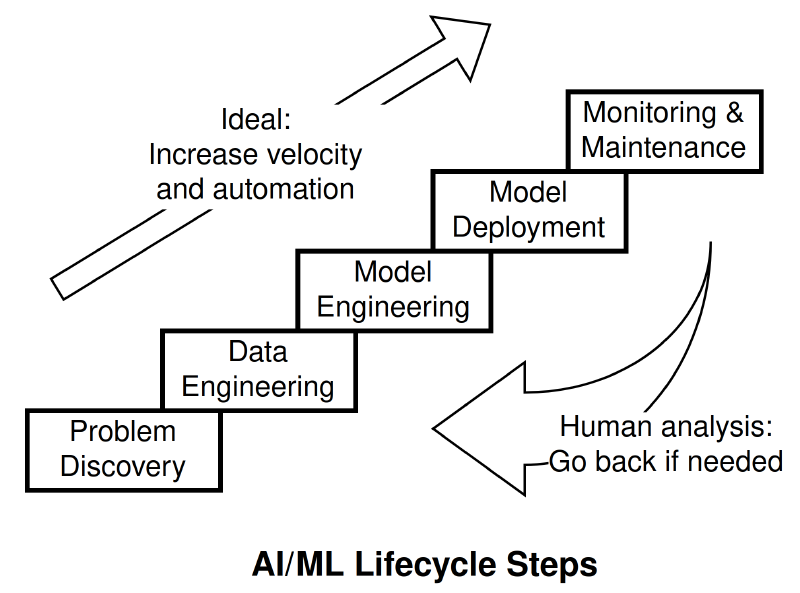

I went through a couple of iterations of refining this idea and landed on the following diagram: Each stage is a step up the AI/ML lifecycle stairs, but analysing the problems that arise can send you tumbling down. It’s a bit like a game of snakes and ladders that is not based purely on luck.

My version of the AI/ML lifecycle: Most arrows are implicit. You go up and down the stairs as reality dictates. Introducing automation to ascend faster on each iteration is the ideal.

Experimentation versus productionisation: Why not both?

The integration of analysis into the lifecycle addresses the second problem noted above, of explicitly accounting for feedback loops. As to the subject of each stage being different, it’d be hard to reshape the AI/ML lifecycle into something as clean as the data engineering lifecycle and still maintain its usefulness. I’m just going to live with that problem.

This leaves us with the third problem, of the need for different mindsets and tools for experimentation and productionisation. There are two types of experiments, though:

- Automated experimentation in production, e.g., via retraining on fresh data or hyperparameter optimisation.

- Human experimentation in analysis environments, e.g., testing different prompts, trying a different modelling approach, or reshaping the data.

Both experiment types have one thing in common: To count as experiments, results need to be centrally logged and fully reproducible. Anything that doesn’t meet the criteria of logging and reproducibility is tinkering, not experimentation. Tinkering is fine early on, but it doesn’t scale – and notebooks are the tool that epitomises tinkering.

Where does this leave us on the problem of different mindsets and tooling, though? Well, it’s hard to capture in a single diagram without overcomplicating things. I realised that this problem requires introducing an additional dimension of maturity:

- Low maturity: Tinkering is fine, as it’s unclear if the model will make it to production. Tinker quickly with whatever tools you’re comfortable with to gain confidence that going to production is feasible and desirable.

- Medium maturity: Log the experiments and datasets that lead to production models, ensuring reproducibility by other humans in clean environments. If anything changes based on production feedback, all new experiments should be logged.

- High maturity: Automate experiments in production. Fully replicate production pipelines for offline human analysis and experimentation.

As a rough guide, the following table summarises the level of human touch on a 1-5 scale, as a function of stage and maturity level (1: low touch & high automation). Here, I followed CRISP-ML(Q)’s separation of offline evaluation from model engineering to emphasise the difference in human touch across maturity levels.

| Stage | Low maturity | Medium maturity | High maturity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Problem discovery | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Data engineering | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| Model engineering | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| Offline evaluation | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Model deployment | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Monitoring & maintenance | 2 | 1 | 1 |

In short, ascending the levels of maturity requires more automation – which is often made easier by introducing more tools and enforcing well-defined processes. For example, MLflow is one toolset that as of the time of this writing, offers features like experiment tracking and a model registry. However, many alternatives exist in the 2024 MAD landscape (machine learning, artificial intelligence, and data). As Jason Corso observed: MLOps tools are a fragmented mess, and no vendor has built an end-to-end solution (despite any marketing claims). This may no longer be the case if you’re reading this 5-10 years from now. However, I doubt that the basic idea of increased automation, tooling, and process definition as a function of increased maturity is going to change radically.

Aside: Isn’t everything different with large language models?

Short answer: No.

Longer answer: Using pretrained models (either language-only or multimodal) doesn’t inherently change the lifecycle stages. It just speeds up or obviates some tasks (see the bottom of the CRISP-ML(Q) article for a comprehensive task list). For example, if you’re using a pretrained model as a black box (without fine-tuning), your model engineering stage would only involve model evaluation and prompt engineering. All stages are still required for success beyond the prototype.

Conclusion

Unlike some of my other posts, this has been an exercise in public writing with the purpose of figuring something out. Thank you for coming along for the ride!

My main takeaways are:

- Accept that human analysis may take you down the AI/ML lifecycle stairs.

- Aim for increased automation to improve rigour as the maturity of your AI/ML lifecycle increases.

- Incrementally adopt tools to support reproducible experimentation and analysis, but avoid premature optimisation.

- The AI/ML lifecycle can’t be simplified to the level of the data engineering lifecycle because the former includes the latter.

- When diagnosing AI/ML lifecycle problems, query how human analysis is done, and identify opportunities for automation that align with business needs.

- If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it: There’s nothing wrong with remaining at a low automation level if the cost of introducing more tools and processes outweighs the likely returns.

As to the problem of running effective diagnoses, I discovered that the people behind the CRISP-ML(Q) lifecycle model have also published an MLOps Stack Canvas, which includes a bunch of questions that go deep into the practical implementation of the lifecycle. I will use some of them to guide my diagnoses in the future, with the depth of the investigation informed by the maturity level.

Public comments are closed, but I love hearing from readers. Feel free to contact me with your thoughts.