Amidst the buzz about new AI models and features, there’s also a constant stream of news about prompt injection attacks. And the victims of those attacks aren’t just scrappy new startups. Even established players like Microsoft and Atlassian have released vulnerable AI software in recent months.

On an individual level, even seasoned engineers such as Steve Yegge can fall victim to complacency when using AI, as shown by this story (emphasis mine):

So one of my favorite things to do is give my coding agents more and more permissions and freedom, just to see how far I can push their productivity without going too far off the rails. It’s a delicate balance. I haven’t given them direct access to my bank account yet. But I did give one access to my Google Cloud production instances and systems. And it promptly wiped a production database password and locked my network.

Put together, this means that as of 2025, we can’t trust AI agents to act securely, no matter how strict our prompts are.

To dive deeper into this topic, I recently led a discussion at the Brisbane AI Paper Reading group around Design Patterns for Securing LLM Agents against Prompt Injections. My slides are here. This post follows the same flow as the slides, covering key concepts, the design patterns from the paper, and a recommended activity to go deep into several case studies.

Key concepts

When talking about AI agent security, we should start by defining AI agents. I like the definition from Anthropic: AI agents are models using tools in a loop. We are essentially dealing with tokens in / tokens out machines. Tokens are numbers that represent parts of words (or other numerical representations of inputs and outputs, such as images). Current models accept an input as a sequence of tokens and produce an output as a sequence of tokens, based on complex mathematical functions. And therein lies the problem: We can’t know for certain what tokens are going to come out of the model.

The paper defines prompt injections as attacks that “occur when adversaries introduce instructions into the content processed by an LLM, causing it to deviate from its intended behavior. Most of these attacks insert malicious instructions to an otherwise benign user prompt, analogously to an SQL injection (thus, the name).”

Similarly to SQL injections, prompt injections can be direct (i.e., done by a malicious or compromised user) or indirect (i.e., inserted into the prompt from documents planted by the attacker). However, there is a key difference between SQL and prompt injections: In SQL, escaping inputs works deterministically, so we can defend from injections by carefully manipulating inputs to the SQL engine. As current AI models accept token streams as inputs and output probabilistic token streams, we cannot defend from prompt injections only by manipulating the inputs. That is, effective defences against prompt injections have to be designed on a system level, outside the models.

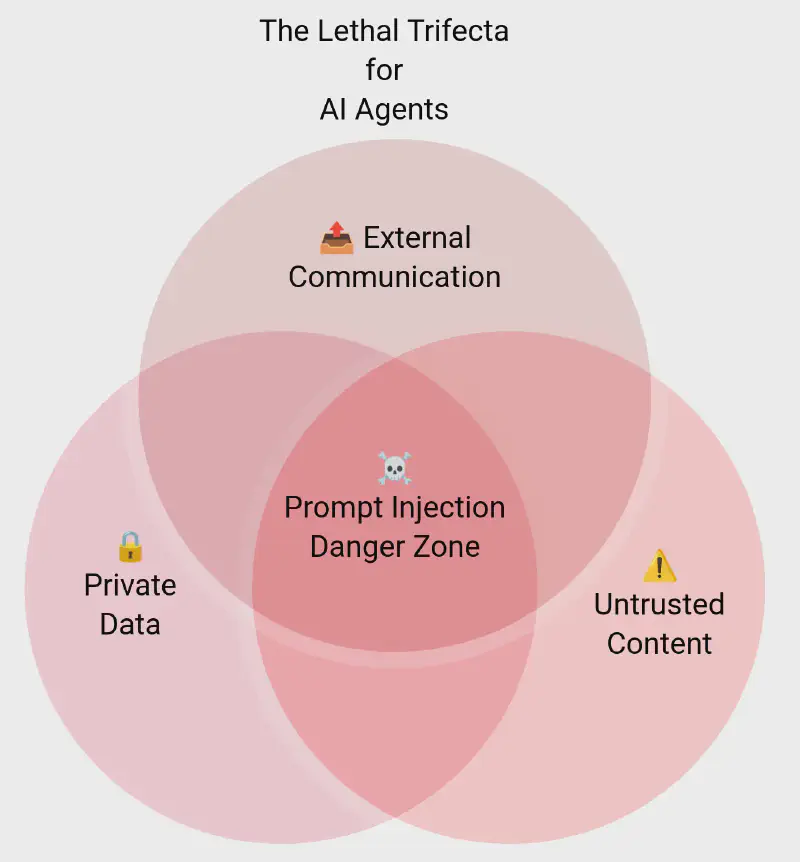

In the early days of the post-ChatGPT AI wave, prompt injection risks were rather benign – typically limited to embarrassing outputs. These days, AI agents are given access to tools, which increases their utility – but also increases potential harm. A great way to conceptualise the potential harm is through what Simon Willison called the lethal trifecta for AI agents:

- Access to your private data.

- Exposure to untrusted content.

- Ability to communicate externally.

Many recent vulnerabilities are due to the combination of these three factors in a single agent. For example, you can build an agent that: (1) reads your emails (access to private data); and (2) sends responses (ability to communicate externally). But since your emails contain untrusted content (as anyone can email you), this opens the door to your private messages getting exfiltrated via prompt injections.

This leads to a simple rule of thumb that both users and AI engineers can apply: Avoid the lethal trifecta! Users should be extra careful with all the shiny new agent products that require broad access, while engineers should design systems that avoid mixing the three elements in a single agent (e.g., by following the design patterns described below).

Avoiding the lethal trifecta is an application of the principle of least privilege: any entity must only be granted access to the resources it needs to complete its tasks. Related to this are the decisions we make on which entities we trust to perform specific tasks.

To drive this point home, ChatGPT and I designed the image in the following slide. Despite my repeated requests, it just wouldn’t spell “wouldn’t” correctly, which serves as a great example of why we should limit our trust of current AI models. While they exhibit greater intelligence than most humans on many fronts, they still make mistakes that intelligent humans wouldn’t make.

The last two key concepts are threat modelling and the balance of security versus utility.

The Threat Modelling Manifesto provides the four key questions to ask when modelling threats:

- What are we working on?

- What can go wrong?

- What are we going to do about it?

- Did we do a good enough job?

When answering these questions, we aim to balance security and utility based on the analysed threats. For example, if we designed a house with thick concrete walls and no doors or windows, its security would be high, but its utility would be low. In most places, houses with lockable doors and windows represent a good balance between security and utility: It isn’t too cumbersome to lock all entry points and carry keys, and the level of security is reasonable for the likely threat of opportunistic break-ins. The same goes with AI agents: The level of acceptable risk depends on the threats and data we’re dealing with, e.g., when I share data with an online chatbot, I accept the risk that it may leak at some point.

Design patterns and best practices

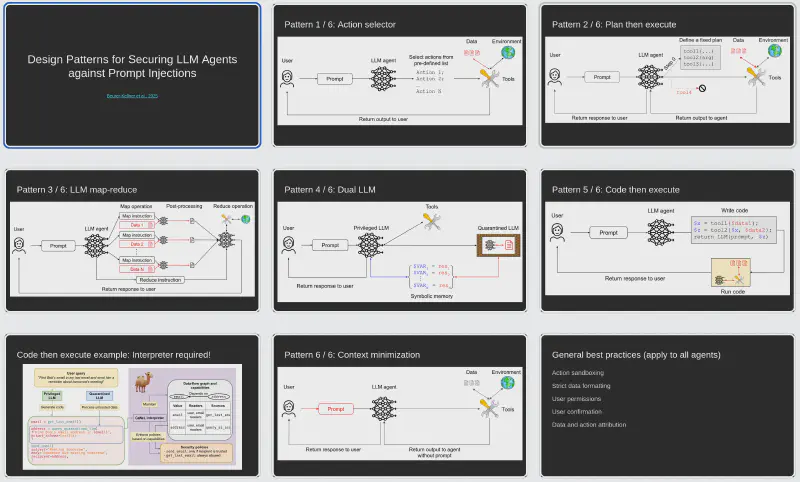

While the key concepts above come from a variety of sources, the best source for understanding the design patterns introduced in the paper is the paper itself. Therefore, I don’t go into too much detail here. Instead, this section serves as a quick reference to the six patterns.

Pattern 1: Action selector. The agent translates incoming requests to pre-defined actions, e.g., a web “chatbot” that responds with links, canned responses, and actual actions the user can already access. This means it can’t do anything more harmful than what the user can do, but it is essentially the same as a dropdown menu with a natural language interface. It’s effective against indirect prompt injection and potentially against direct injection, as there is nothing to gain from injection by a malicious user.

Pattern 2: Plan then execute.

The agent defines a plan and can’t deviate from it based on the untrusted data, e.g., an input like “send today’s schedule to John” becomes calendar.read(today); email.write(..., "john@company").

This doesn’t prevent direct prompt injections, and doesn’t protect from indirect prompt injections that affect the contents of the email.

Whether this pattern is good enough depends on the threat model.

Pattern 3: LLM map-reduce. Only isolated agents (the mappers) interact with untrusted data. Their outputs are restricted to prevent prompt injections (e.g., using regular expressions or strict typing). For example, when handling a request like “find all files that contain an invoice and email me the list of filenames”, the main agent doesn’t have access to the contents of the files. Instead, it invokes isolated mapper agents that read each file and return a boolean. The final reduce operation produces a safe list based on the trusted boolean inputs (assuming filenames are trusted).

Pattern 4: Dual LLM. This is a more general version of the map-reduce pattern, where the privileged LLM doesn’t see the untrusted data. The quarantined LLM sees the data, but only communicates about it using symbols. For example, when handling a request like “find email addresses in this (potentially untrusted) document”, the quarantined LLM sees the contents of the document and returns variables with the email addresses (which match strict patterns). The privileged LLM only sees the trusted variable names, so it’s not affected by the contents of the document.

Pattern 5: Code then execute. This is a generalisation of the previous three patterns, where the main agent writes a formal computer program that isolates untrusted input processing to unprivileged agents. The implementation isn’t trivial: this pattern comes from the 125-page paper that introduced the CaMeL interpreter (“a custom Python interpreter that operates over a restricted version of Python”). I haven’t read the full CaMeL paper, but my understanding is that it requires defining specific security policies to be fully effective. Therefore, practical implementations depend on the use case and threat model.

Pattern 6: Context minimization. Like Simon Willison, I found the description of this pattern to be a bit confusing. My understanding is that in this case the prompt may be malicious, so it’s removed from the tool response. However, the example given in the paper seems a bit convoluted, as it includes prompt-injecting a customer service agent to give the user a quote with a large discount. This assumes a company would go be willing to go with whatever discounts given by its bots. This is a scenario that should be handled via other means (like deterministic guardrails), as we’re not yet at the point where we can trust AI agents in customer-facing roles.

General best practices. The authors emphasise that while different design patterns apply based on the use case, the following best practices should apply to any agent to the extent possible.

- Action sandboxing: Applying the principle of least privilege in practice, by running specific agent actions in sandboxed environments with limited permissions.

- Strict data formatting: Using deterministic code to ensure that expected schema rules are followed, rather than allowing arbitrary text.

- User permissions: Limiting the agent’s permissions to those of the authenticated user, so it can only do what the user can do. This reduces the potential harm from prompt injection attacks.

- User confirmation: Asking the user before running actions that are potentially harmful. While this is useful in some scenarios, it increases friction and reduces automation. Further, excessive requests for confirmation increase the chance of users ignoring the content of the confirmation requests (as most of us do when asked to read the terms of service).

- Data and action attribution: Providing explanations to the user on the reasoning of the agent (though this may also lead to user fatigue).

All the design pattern slides in one image.

Case study activity

Consuming information about design patterns only takes you so far. It’s already better than vibe coding and hoping for the best, but applying patterns in reality is the way to truly learn them.

To simulate this at the AI paper event, I split the attendees to groups. I then assigned each group one of the case studies discussed in the paper (§4.2 data analyst, §4.3 email and calendar assistant, §4.4 customer service representative, §4.5 booking agent, and §4.6 product recommender), and prompted each group with the following tasks.

- Define the capabilities and scope of the agent: What can a human agent do?

- Identify the threats, focusing on direct and indirect prompt injections.

- Discuss mitigations using the patterns and best practices.

- Present the approach that best balances security and utility.

I was pleased with the lively discussion that this activity sparked! 🎉

You can also try this at home: Discuss the above points with colleagues or with your favourite chatbot. Prompted well, they can be surprisingly effective at poking holes in your thinking. Just don’t trust them with unbounded access to your key accounts (yet).

Public comments are closed, but I love hearing from readers. Feel free to contact me with your thoughts.